Info

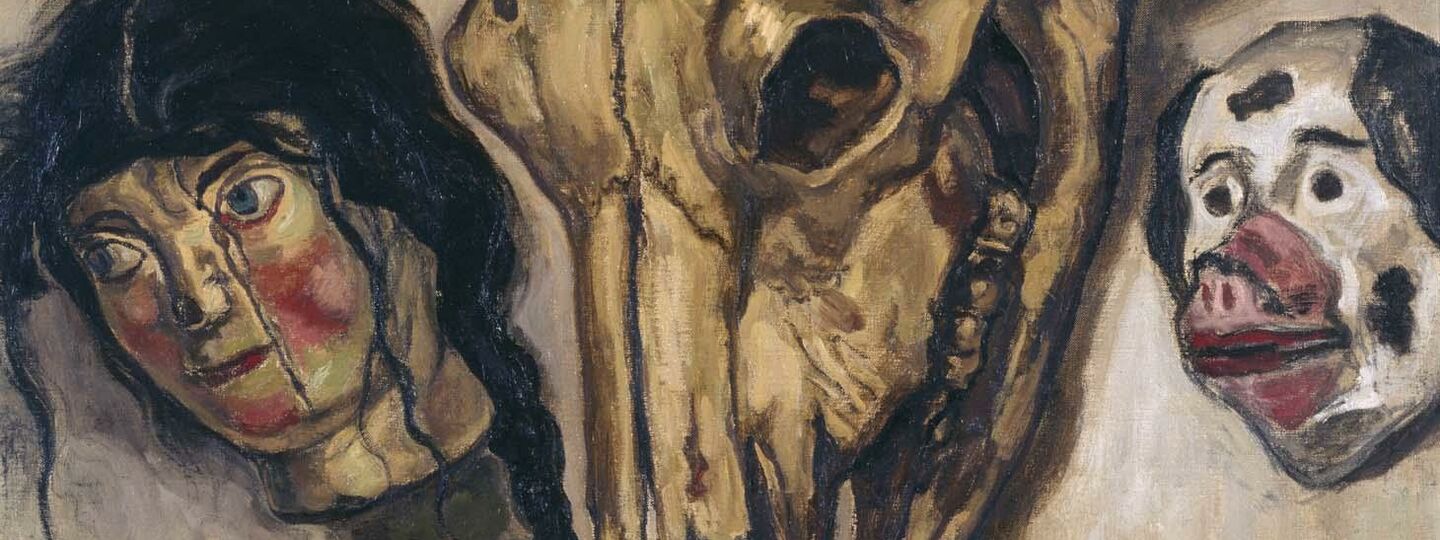

Teste e maschere

José Gutiérrez-Solana

1943

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

José Asunción Silva (Bogotá, 1865 - 1896) Poeta colombiano. En la historiografía literaria suele reconocérsele como el gran iniciador del modernismo en Hispanoamérica, que el nicaragüense Rubén Darío llevaría a la cúspide. Dotado de una gran sensibilidad humana y artística y de una notable inteligencia, tuvo una formación literaria precoz, resultado de un ambiente familiar cultivado y creativo. Se suicidó a sus 30 años dándose un tiro en el corazón con un revólver Smith & Wesson, y se cuenta que se encontró el libro El Triunfo de la muerte de Gabriele D'Annunzio, a la cabecera de su lecho. Su suicidio se debió a su escasez de dinero, entre otras variadas causas detalladas por expertos y conocidos suyos y del medio social bogotano de la época.

Leopoldo Lugones fue un poeta, ensayista, periodista y político argentino. Nació el 13 de junio de 1874 en la localidad de Villa María del Río Seco ubicada en el norte de la provincia de Córdoba, como el primer hijo de Santiago M. Lugones y Custodia Argüello. Decepcionado, precisamente, por las circunstancias políticas de la década de 1930 y quizás por su propia militancia, se suicida el 18 de febrero de 1938 en un hotel de Tigre, Buenos Aires, (llamado "El Tropezón") al ingerir una mezcla de cianuro y whisky.

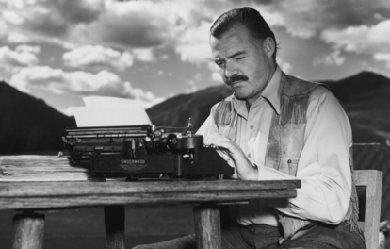

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (November 10, 1879– December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern singing poetry, as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted. Crushed by financial worry and in failing health from his six-month road trip, Lindsay sank into depression. While in New York in 1905 Lindsay turned to poetry in earnest. He tried to sell his poems on the streets. Self-printing his poems, he began to barter a pamphlet titled “Rhymes To Be Traded For Bread”, which he traded for food as a self-perceived modern version of a medieval troubadour. On December 5, 1931, he committed suicide by drinking a bottle of Lysol. His last words were: “They tried to get me; I got them first!”

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father, who worked as a bank clerk, was also an artist, scholar, antiquarian, and collector of books and pictures. His rare book collection of more than 6,000 volumes included works in Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish. Much of Browning's education came from his well-read father. It is believed that he was already proficient at reading and writing by the age of five. A bright and anxious student, Browning learned Latin, Greek, and French by the time he was fourteen. From fourteen to sixteen he was educated at home, attended to by various tutors in music, drawing, dancing, and horsemanship.

Isaac Watts (17 July 1674– 25 November 1748) was an English Christian minister, hymnwriter, theologian and logician. A prolific and popular hymn writer, his work was part of evangelization. He was recognized as the “Father of English Hymnody”, credited with some 750 hymns. Many of his hymns remain in use today and have been translated into numerous languages.

Alda Giuseppina Angela Merini (Milano, 21 marzo 1931 – Milano, 1º novembre 2009) è stata una poetessa, aforista e scrittrice italiana. «Ho la sensazione di durare troppo, di non riuscire a spegnermi: come tutti i vecchi le mie radici stentano a mollare la terra. Ma del resto dico spesso a tutti che quella croce senza giustizia che è stato il mio manicomio non ha fatto che rivelarmi la grande potenza della vita.»

Dolores Veintimilla de Galindo (Quito, 12 de julio de 1829 - Cuenca, 23 de mayo de 1857) fue una poeta ecuatoriana del siglo XIX. Durante su corta vida fue la creadora de poemas de corte romántico que están cargados de elementos que asocian a la mujer con el papel de víctima asociados con sentimientos de dolor, tristeza, anhelo del pasado, amores frustrado y pesimismo. Fue influenciada por la formación de la subjetividad femenina de su época. Su poema “Quejas” está lleno de esos sentimientos que reflejan su estado anímico. El fracaso en su matrimonio con el médico colombiano Sixto Galindo, así como su pensamiento feminista adelantado a la época, marcarían la personalidad y los trabajos posteriores de Dolores. La persecución e incomprensión de la sociedad cuencana la llevó al suicidio.

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, Time observed: "Whenever possible Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out." Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brown, and wrote on apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognised the wide appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an "orthodox" Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting to Roman Catholicism from high church Anglicanism. Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, John Henry Newman and John Ruskin.

.jpeg?locale=it)

Thomas Moore (28 May 1779 – 25 February 1852), also known as Tom Moore, was an Irish writer, poet, and lyricist celebrated for his Irish Melodies. His setting of English-language verse to old Irish tunes marked the transition in popular Irish culture from Irish to English. Politically, Moore was recognised in England as a press, or "squib", writer for the aristocratic Whigs; in Ireland he was accounted a Catholic patriot.

Edwin Arlington Robinson (December 22, 1869—April 6, 1935) was an American poet who won three Pulitzer Prizes for his work. He was born in Head Tide, Lincoln County, Maine but his family moved to Gardiner, Maine in 1871. He described his childhood in Maine as “stark and unhappy”: His parents (who had wanted a girl) did not name him until he was six months old, when they visited a holiday resort—whereupon, other vacationers decided that he should have a name and selected a man from Arlington, Massachusetts to draw a name out of a hat. Throughout his life, he not only hated his given name, but also his family’s habit of calling him “Win.” As an adult, he always used the signature “E. A.”

Alan Alexander “A. A.” Milne (/ˈmɪln/; 18 January 1882– 31 January 1956) was an English author, best known for his books about the teddy bear Winnie-the-Pooh and for various poems. Milne was a noted writer, primarily as a playwright, before the huge success of Pooh overshadowed all his previous work. Milne served in both World Wars, joining the British Army in World War I, and was a captain of the British Home Guard in World War II. Biography Alan Alexander Milne was born in Kilburn, London to parents John Vince Milne, who was Scottish, and Sarah Marie Milne (née Heginbotham) and grew up at Henley House School, 6/7 Mortimer Road (now Crescent), Kilburn, a small public school run by his father. One of his teachers was H. G. Wells, who taught there in 1889–90. Milne attended Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge where he studied on a mathematics scholarship, graduating with a B.A. in Mathematics in 1903. While there, he edited and wrote for Granta, a student magazine. He collaborated with his brother Kenneth and their articles appeared over the initials AKM. Milne’s work came to the attention of the leading British humour magazine Punch, where Milne was to become a contributor and later an assistant editor. Milne played for the amateur English cricket team the Allahakbarries alongside authors J. M. Barrie and Arthur Conan Doyle. Milne joined the British Army in World War I and served as an officer in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and later, after a debilitating illness, the Royal Corps of Signals. He was commissioned into the 4th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment on 17 February 1915 as a second lieutenant (on probation). His commission was confirmed on 20 December 1915. On 7 July 1916, he was injured while serving in the Battle of the Somme and invalided back to England. Having recuperated, he was recruited into Military Intelligence to write propaganda articles for MI 7b between 1916 and 1918. He was discharged on 14 February 1919, and settled in Mallord Street, Chelsea. He relinquished his commission on 19 February 1920, retaining the rank of lieutenant. After the war, he wrote a denunciation of war titled Peace with Honour (1934), which he retracted somewhat with 1940's War with Honour. During World War II, Milne was one of the most prominent critics of fellow English writer P. G. Wodehouse, who was captured at his country home in France by the Nazis and imprisoned for a year. Wodehouse made radio broadcasts about his internment, which were broadcast from Berlin. Although the light-hearted broadcasts made fun of the Germans, Milne accused Wodehouse of committing an act of near treason by cooperating with his country’s enemy. Wodehouse got some revenge on his former friend (e.g., in The Mating Season) by creating fatuous parodies of the Christopher Robin poems in some of his later stories, and claiming that Milne “was probably jealous of all other writers.... But I loved his stuff.” Milne married Dorothy “Daphne” de Sélincourt in 1913 and their son Christopher Robin Milne was born in 1920. In 1925, A. A. Milne bought a country home, Cotchford Farm, in Hartfield, East Sussex. During World War II, A. A. Milne was Captain of the British Home Guard in Hartfield & Forest Row, insisting on being plain “Mr. Milne” to the members of his platoon. He retired to the farm after a stroke and brain surgery in 1952 left him an invalid, and by August 1953 “he seemed very old and disenchanted”. Milne died in January 1956, aged 74. Literary career 1903 to 1925 After graduating from Cambridge in 1903, A. A. Milne contributed humorous verse and whimsical essays to Punch, joining the staff in 1906 and becoming an assistant editor. During this period he published 18 plays and 3 novels, including the murder mystery The Red House Mystery (1922). His son was born in August 1920 and in 1924 Milne produced a collection of children’s poems When We Were Very Young, which were illustrated by Punch staff cartoonist E. H. Shepard. A collection of short stories for children Gallery of Children, and other stories that became part of the Winnie-the-Pooh books, were first published in 1925. Milne was an early screenwriter for the nascent British film industry, writing four stories filmed in 1920 for the company Minerva Films (founded in 1920 by the actor Leslie Howard and his friend and story editor Adrian Brunel). These were The Bump, starring Aubrey Smith; Twice Two; Five Pound Reward; and Bookworms. Some of these films survive in the archives of the British Film Institute. Milne had met Howard when the actor starred in Milne’s play Mr Pim Passes By in London. Looking back on this period (in 1926), Milne observed that when he told his agent that he was going to write a detective story, he was told that what the country wanted from a “Punch humorist” was a humorous story; when two years later he said he was writing nursery rhymes, his agent and publisher were convinced he should write another detective story; and after another two years, he was being told that writing a detective story would be in the worst of taste given the demand for children’s books. He concluded that “the only excuse which I have yet discovered for writing anything is that I want to write it; and I should be as proud to be delivered of a Telephone Directory con amore as I should be ashamed to create a Blank Verse Tragedy at the bidding of others.” 1926 to 1928 Milne is most famous for his two Pooh books about a boy named Christopher Robin after his son, Christopher Robin Milne, and various characters inspired by his son’s stuffed animals, most notably the bear named Winnie-the-Pooh. Christopher Robin Milne’s stuffed bear, originally named “Edward”, was renamed “Winnie-the-Pooh” after a Canadian black bear named Winnie (after Winnipeg), which was used as a military mascot in World War I, and left to London Zoo during the war. “The pooh” comes from a swan called “Pooh”. E. H. Shepard illustrated the original Pooh books, using his own son’s teddy, Growler ("a magnificent bear"), as the model. The rest of Christopher Robin Milne’s toys, Piglet, Eeyore, Kanga, Roo and Tigger, were incorporated into A. A. Milne’s stories, and two more characters– Rabbit and Owl– were created by Milne’s imagination. Christopher Robin Milne’s own toys are now under glass in New York where 750,000 people visit them every year. The fictional Hundred Acre Wood of the Pooh stories derives from Five Hundred Acre Wood in Ashdown Forest in East Sussex, South East England, where the Pooh stories were set. Milne lived on the northern edge of the forest at Cotchford Farm, 51.090°N 0.107°E / 51.090; 0.107, and took his son walking there. E. H. Shepard drew on the landscapes of Ashdown Forest as inspiration for many of the illustrations he provided for the Pooh books. The adult Christopher Robin commented: “Pooh’s Forest and Ashdown Forest are identical”. Popular tourist locations at Ashdown Forest include: Galleon’s Lap, The Enchanted Place, the Heffalump Trap and Lone Pine, Eeyore’s Sad and Gloomy Place, and the wooden Pooh Bridge where Pooh and Piglet invented Poohsticks. Not yet known as Pooh, he made his first appearance in a poem, “Teddy Bear”, published in Punch magazine in February 1924. Pooh first appeared in the London Evening News on Christmas Eve, 1925, in a story called “The Wrong Sort Of Bees”. Winnie-the-Pooh was published in 1926, followed by The House at Pooh Corner in 1928. A second collection of nursery rhymes, Now We Are Six, was published in 1927. All three books were illustrated by E. H. Shepard. Milne also published four plays in this period. He also “gallantly stepped forward” to contribute a quarter of the costs of dramatising P. G. Wodehouse’s A Damsel in Distress. The World of Pooh won the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award in 1958. 1929 onwards The success of his children’s books was to become a source of considerable annoyance to Milne, whose self-avowed aim was to write whatever he pleased and who had, until then, found a ready audience for each change of direction: he had freed pre-war Punch from its ponderous facetiousness; he had made a considerable reputation as a playwright (like his idol J. M. Barrie) on both sides of the Atlantic; he had produced a witty piece of detective writing in The Red House Mystery (although this was severely criticised by Raymond Chandler for the implausibility of its plot). But once Milne had, in his own words, "said goodbye to all that in 70,000 words" (the approximate length of his four principal children’s books), he had no intention of producing any reworkings lacking in originality, given that one of the sources of inspiration, his son, was growing older. In his literary home, Punch, where the When We Were Very Young verses had first appeared, Methuen continued to publish whatever Milne wrote, including the long poem “The Norman Church” and an assembly of articles entitled Year In, Year Out (which Milne likened to a benefit night for the author). In 1930, Milne adapted Kenneth Grahame’s novel The Wind in the Willows for the stage as Toad of Toad Hall. The title was an implicit admission that such chapters as Chapter 7, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn”, could not survive translation to the theatre. A special introduction written by Milne is included in some editions of Grahame’s novel. Legacy and commemoration The rights to A. A. Milne’s Pooh books were left to four beneficiaries: his family, the Royal Literary Fund, Westminster School and the Garrick Club. After Milne’s death in 1956, one week and six days after his 74th birthday, his widow sold her rights to the Pooh characters to Stephen Slesinger, whose widow sold the rights after Slesinger’s death to the Walt Disney Company, which has made many Pooh cartoon movies, a Disney Channel television show, as well as Pooh-related merchandise. In 2001, the other beneficiaries sold their interest in the estate to the Disney Corporation for $350m. Previously Disney had been paying twice-yearly royalties to these beneficiaries. The estate of E. H. Shepard also received a sum in the deal. The copyright on Pooh expires in 2026. In 2008, a collection of original illustrations featuring Winnie-the-Pooh and his animal friends sold for more than £1.2 million at auction in Sotheby’s, London. Forbes magazine ranked Winnie the Pooh the most valuable fictional character in 2002; Winnie the Pooh merchandising products alone had annual sales of more than $5.9 billion. In 2005, Winnie the Pooh generated $6 billion, a figure surpassed by only Mickey Mouse. A memorial plaque in Ashdown Forest, unveiled by Christopher Robin in 1979, commemorates the work of A. A. Milne and Shepard in creating the world of Pooh. Milne once wrote of Ashdown Forest: “In that enchanted place on the top of the forest a little boy and his bear will always be playing”. In 2003, Winnie the Pooh was listed at number 7 on the BBC’s survey The Big Read. In 2006, Winnie the Pooh received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, marking the 80th birthday of Milne’s creation. That same year a UK poll saw Winnie the Pooh voted onto the list of icons of England. Several of Milne’s children’s poems were set to music by the composer Harold Fraser-Simson. His poems have been parodied many times, including with the books When We Were Rather Older and Now We Are Sixty. The 1963 film The King’s Breakfast was based on Milne’s poem of the same name. Religious views Milne did not speak out much on the subject of religion, although he used religious terms to explain his decision, while remaining a pacifist, to join the British Home Guard: “In fighting Hitler”, he wrote, “we are truly fighting the Devil, the Anti-Christ... Hitler was a crusader against God.” His best known comment on the subject was recalled on his death: The Old Testament is responsible for more atheism, agnosticism, disbelief—call it what you will—than any book ever written; it has emptied more churches than all the counter-attractions of cinema, motor bicycle and golf course. He also wrote the poem “Explained”: Works Novels * Lovers in London (1905. Some consider this more of a short story collection; Milne did not like it and considered The Day’s Play as his first book.) * Once on a Time (1917) * Mr. Pim (1921) (A novelisation of his play Mr. Pim Passes By (1919)) * The Red House Mystery (1922) * Two People (1931) (Inside jacket claims this is Milne’s first attempt at a novel.) * Four Days’ Wonder (1933) * Chloe Marr (1946) Non-fiction * Peace With Honour (1934) * It’s Too Late Now: The Autobiography of a Writer (1939) * War With Honour (1940) * War Aims Unlimited (1941) * Year In, Year Out (1952) (illustrated by E. H. Shepard) Punch articles * The Day’s Play (1910) * Once A Week (1914) * The Holiday Round (1912) * The Sunny Side (1921) * Those Were the Days (1929) [The four volumes above, compiled] Newspaper articles and book introductions * The Chronicles of Clovis by “Saki” (1911) [Introduction to] * Not That It Matters (1920) * By Way of Introduction (1929) Story collections for children * A Gallery of Children (1925) * Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) (illustrated by Ernest H. Shepard) * The House at Pooh Corner (1928) (illustrated by E. H. Shepard) * Short Stories Poetry collections for children * When We Were Very Young (1924) (illustrated by E. H. Shepard) * Now We Are Six (1927) (illustrated by E. H. Shepard) Story collections * The Secret and other stories (1929) * The Birthday Party (1948) * A Table Near the Band (1950) Poetry * For the Luncheon Interval [poems from Punch] * When We Were Very Young (1924) (illustrated by E. H. Shepard) * Now We Are Six (1927) (illustrated by E. H. Shepard) * Behind the Lines (1940) * The Norman Church (1948) * “The Knight Whose Armor Didn’t Squeak” Screenplays and plays * Wurzel-Flummery (1917) * Belinda (1918) * The Boy Comes Home (1918) * Make-Believe (1918) (children’s play) * The Camberley Triangle (1919) * Mr. Pim Passes By (1919) * The Red Feathers (1920) * The Bump (1920, Minerva Films), starring Aubrey Smith * Twice Two (1920, Minerva Films) * Five Pound Reward (1920, Minerva Films) * Bookworms (1920, Minerva Films) * The Great Broxopp (1921) * The Dover Road (1921) * The Lucky One (1922) * The Truth About Blayds (1922) * The Artist: A Duologue (1923) * Give Me Yesterday (1923) (a.k.a. Success in the UK) * Ariadne (1924) * The Man in the Bowler Hat: A Terribly Exciting Affair (1924) * To Have the Honour (1924) * Portrait of a Gentleman in Slippers (1926) * Success (1926) * Miss Marlow at Play (1927) * The Fourth Wall or The Perfect Alibi (1928) (later adapted for the film Birds of Prey (1930), directed by Basil Dean) * The Ivory Door (1929) * Toad of Toad Hall (1929) (adaptation of The Wind in the Willows) * Michael and Mary (1930) * Other People’s Lives (1933) (a.k.a. They Don’t Mean Any Harm) * Miss Elizabeth Bennet (1936) [based on Pride and Prejudice] * Sarah Simple (1937) * Gentleman Unknown (1938) * The General Takes Off His Helmet (1939) in The Queen’s Book of the Red Cross * The Ugly Duckling (1941) * Before the Flood (1951). References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._A._Milne

Arturo Borja Pérez, (n. Quito, 1892 - f. Ibídem, 13 de noviembre de 1912) fue un poeta ecuatoriano, perteneciente al movimiento llamado “La Generación Decapitada” y el primero del grupo en despuntar como modernista. Es muy escasa su obra artística pero suficiente para determinar la calidad de poeta: una corona de veinte composiciones forma el libro titulado La flauta de ónix, y seis poemas más; obras que fueron publicadas póstumamente. Se suicidó en la ciudad de Quito, el 13 de noviembre de 1912, contando apenas con 20 años de edad. Ofrenda de rosas (A Arturo Borja) Recuerdo que te hallé por mi camino como un Verlaine aún adolescente, ¡y daba el signo de un fatal destino tu alma de estirpe lírica y ardiente! Y ambos fraternizamos; que tus rosas para todas las almas entreabrías, ¡haciéndote en las horas humildosas dueño de todas las melancolías...! Quién volviera a tus ojos, en ofrenda, la vida humilde que suspira y canta, como el Rubí de manos de leyenda que antaño dijo a Lázaro: ¡Levanta! Evoco el sueño juvenil de un día que, en el Claustro del Arte bien sentido, matamos la viril hipocrecía, y laboramos lentos el gemido. Y ahora la luna de tu sistro agrestre, al visitar nuestro santurario frío, da su color de lágrima celeste en el cristal de tu crisol vacío... ¡Adiós, fuente de lánguido quebranto!, que volvías un Fénix mi rosal, ¡encantando las rosas sin encanto cuando el encanto huía con el mal! ¡Adiós, fuente de lágrimas cantoras que halagaron el viaje juvenil!; de la angustia de Abril refrescadoras como lluvias caídas en Abril... Duerme y reposa; que quizás es bueno sólo el sueño sin sueño en que caíste, ¡la flor de espino y el laurel de heleno entremezclados en tu frente triste! —Humberto Fierro Feliz tú, hermano mío (Al espíritu fraternal de Arturo Borja) Poeta, hermano mío, que como yo sufriste, el frío del vacío y la grandeza triste de saberte una nube en prisión de rocío; tu buen hermano en lira, en rosa, azul y luna que inspira la mentira de la verde laguna, sabe envidiar tu suerte porque tu suerte admira. Lloro tu vida breve por lo que dado hubieras, pero la leve nieve de tus quimeras en nube se transforma y desde lo alto llueve. Poeta, hermano mío, ya no estarás más triste, ni el frío del vacío sentirás que sentiste... Ya no eres una nube encerrada en rocío; después de que partiste tu lluvia se hizo un río que da savia a tu rosa y a tu bulbul alpiste... ¡Feliz tú, hermano mío! —Alejandro Sux

Vicente Pío Marcelino Cirilo Aleixandre y Merlo (Sevilla, 26 de abril de 1898 – Madrid, 13 de diciembre de 1984) fue un poeta español de la llamada Generación del 27. Elegido académico en sesión del día 30 de junio de 1949, ingresó en la Real Academia Española el 22 de enero de 1950. Ocupó el sillón de la letra O. Premio Nacional de Literatura en 1933 por La destrucción o el amor, Premio de la Crítica en 1963 por En un vasto dominio, y en 1969, por Poemas de la consumación, y Premio Nobel de Literatura en 1977.

Celia Laighton Thaxter (June 29, 1835 – August 25, 1894) was an American writer of poetry and stories. She was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thaxter grew up in the Isles of Shoals, first on White Island, where her father, Thomas Laighton, was a lighthouse keeper, and then on Smuttynose and Appledore Islands. When she was sixteen, she married Levi Thaxter and moved to the mainland, residing first in Watertown, Massachusetts at a property his father owned. Celia died suddenly while on Appledore Island. She was buried not far from her cottage, which unfortunately burned in the 1914 fire that destroyed The Appledore House hotel.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882) was an American essayist, lecturer, and poet, who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism and a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society, and he disseminated his thoughts through dozens of published essays and more than 1, public lectures across the United States. Emerson gradually moved away from the religious and social beliefs of his contemporaries, formulating and expressing the philosophy of Transcendentalism in his 1836 essay, Nature. Following this ground-breaking work, he gave a speech entitled The American Scholar in 1837, which Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. considered to be America's "Intellectual Declaration of Independence". Emerson wrote most of his important essays as lectures first, then revised them for print. His first two collections of essays – Essays: First Series and Essays: Second Series, published respectively in 1841 and 1844 – represent the core of his thinking, and include such well-known essays as Self-Reliance, The Over-Soul, Circles, The Poet and Experience. Together with Nature, these essays made the decade from the mid-1830s to the mid-1840s Emerson's most fertile period. Emerson wrote on a number of subjects, never espousing fixed philosophical tenets, but developing certain ideas such as individuality, freedom, the ability for humankind to realize almost anything, and the relationship between the soul and the surrounding world. Emerson's "nature" was more philosophical than naturalistic; "Philosophically considered, the universe is composed of Nature and the Soul." While his writing style can be seen as somewhat impenetrable, and was thought so even in his own time, Emerson's essays remain among the linchpins of American thinking, and Emerson's work has greatly influenced the thinkers, writers and poets that have followed him. When asked to sum up his work, he said his central doctrine was "the infinitude of the private man.” Early life, family, and education Emerson was born in Boston, Massachusetts on May 25, 1803, son of Ruth Haskins and the Rev. William Emerson, a Unitarian minister. He was named after his mother's brother Ralph and the father's great-grandmother Rebecca Waldo. Ralph Waldo was the second of five sons who survived into adulthood; the others were William, Edward, Robert Bulkeley, and Charles. Three other children—Phebe, John Clarke, and Mary Caroline–died in childhood. The young Ralph Waldo Emerson's father died from stomach cancer on May 12, 1811, less than two weeks before Emerson's eighth birthday. Emerson was raised by his mother, with the help of the other women in the family; his aunt Mary Moody Emerson in particular had a profound effect on Emerson. She lived with the family off and on, and maintained a constant correspondence with Emerson until her death in 1863. Emerson's formal schooling began at the Boston Latin School in 1812 when he was nine. In October 1817, at 14, Emerson went to Harvard College and was appointed freshman messenger for the president, requiring Emerson to fetch delinquent students and send messages to faculty. Midway through his junior year, Emerson began keeping a list of books he had read and started a journal in a series of notebooks that would be called "Wide World". He took outside jobs to cover his school expenses, including as a waiter for the Junior Commons and as an occasional teacher working with his uncle Samuel in Waltham, Massachusetts. By his senior year, Emerson decided to go by his middle name, Waldo. Emerson served as Class Poet; as was custom, he presented an original poem on Harvard's Class Day, a month before his official graduation on August 29, 1821, when he was 18. He did not stand out as a student and graduated in the exact middle of his class of 59 people. In 1826, faced with poor health, Emerson went to seek out warmer climates. He first went to Charleston, South Carolina, but found the weather was still too cold. He then went further south, to St. Augustine, Florida, where he took long walks on the beach, and began writing poetry. While in St. Augustine, he made the acquaintance of Prince Achille Murat. Murat, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, was only two years his senior; they became extremely good friends and enjoyed one another's company. The two engaged in enlightening discussions on religion, society, philosophy, and government, and Emerson considered Murat an important figure in his intellectual education. While in St. Augustine, Emerson had his first experience of slavery. At one point, he attended a meeting of the Bible Society while there was a slave auction taking place in the yard outside. He wrote, "One ear therefore heard the glad tidings of great joy, whilst the other was regaled with 'Going, gentlemen, going’!” Early career After Harvard, Emerson assisted his brother William in a school for young women established in their mother's house, after he had established his own school in Chelmsford, Massachusetts; when his brother William went to Göttingen to study divinity, Emerson took charge of the school. Over the next several years, Emerson made his living as a schoolmaster, then went to Harvard Divinity School. Emerson's brother Edward, two years younger than he, entered the office of lawyer Daniel Webster, after graduating Harvard first in his class. Edward's physical health began to deteriorate and he soon suffered a mental collapse as well; he was taken to McLean Asylum in June 1828 at age 23. Although he recovered his mental equilibrium, he died in 1834 from apparently longstanding tuberculosis. Another of Emerson's bright and promising younger brothers, Charles, born in 1808, died in 1836, also of tuberculosis, making him the third young person in Emerson's innermost circle to die in a period of a few years. Emerson met his first wife, Ellen Louisa Tucker, in Concord, New Hampshire on Christmas Day, 1827, and married her when she was 18. The couple moved to Boston, with Emerson's mother Ruth moving with them to help take care of Ellen, who was already sick with tuberculosis. Less than two years later, Ellen died at the age of 20 on February 8, 1831, after uttering her last words: "I have not forgot the peace and joy." Emerson was heavily affected by her death and visited her grave in Roxbury daily. In a journal entry dated March 29, 1832, Emerson wrote, "I visited Ellen's tomb & opened the coffin." Boston's Second Church invited Emerson to serve as its junior pastor and he was ordained on January 11, 1829. His initial salary was $1, a year, increasing to $1, in July, but with his church role he took on other responsibilities: he was chaplain to the Massachusetts legislature, and a member of the Boston school committee. His church activities kept him busy, though during this period, facing the imminent death of his wife, he began to doubt his own beliefs. After his wife's death, he began to disagree with the church's methods, writing in his journal in June 1832: "I have sometimes thought that, in order to be a good minister, it was necessary to leave the ministry. The profession is antiquated. In an altered age, we worship in the dead forms of our forefathers." His disagreements with church officials over the administration of the Communion service and misgivings about public prayer eventually led to his resignation in 1832. As he wrote, "This mode of commemorating Christ is not suitable to me. That is reason enough why I should abandon it." As one Emerson scholar has pointed out, "Doffing the decent black of the pastor, he was free to choose the gown of the lecturer and teacher, of the thinker not confined within the limits of an institution or a tradition." Emerson toured Europe in 1833 and later wrote of his travels in English Traits (1857). He left aboard the brig Jasper on Christmas Day, 1832, sailing first to Malta. During his European trip, he spent several months in Italy, visiting Rome, Florence and Venice, among other cities. When in Rome, he met with John Stuart Mill, who gave him a letter of recommendation to meet Thomas Carlyle. He went to Switzerland, and had to be dragged by fellow passengers to visit Voltaire's home in Ferney, "protesting all the way upon the unworthiness of his memory." He then went on to Paris, a "loud modern New York of a place,", where he visited the Jardin des Plantes. He was greatly moved by the organization of plants according to Jussieu's system of classification, and the way all such objects were related and connected. As Richardson says, "Emerson's moment of insight into the interconnectedness of things in the Jardin des Plantes was a moment of almost visionary intensity that pointed him away from theology and toward science." Moving north to England, Emerson met William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Thomas Carlyle. Carlyle in particular was a strong influence on Emerson; Emerson would later serve as an unofficial literary agent in the United States for Carlyle, and in March 1835, he tried to convince Carlyle to come to America to lecture. The two would maintain correspondence until Carlyle's death in 1881. Emerson returned to the United States on October 9, 1833, and lived with his mother in Newton, Massachusetts, until October, 1834, when he moved to Concord, Massachusetts, to live with his step-grandfather Dr. Ezra Ripley at what was later named The Old Manse. Seeing the budding Lyceum movement, which provided lectures on all sorts of topics, Emerson saw a possible career as a lecturer. On November 5, 1833, he made the first of what would eventually be some 1, lectures, discussing The Uses of Natural History in Boston. This was an expanded account of his experience in Paris. In this lecture, he set out some of his important beliefs and the ideas he would later develop in his first published essay Nature: Nature is a language and every new fact one learns is a new word; but it is not a language taken to pieces and dead in the dictionary, but the language put together into a most significant and universal sense. I wish to learn this language, not that I may know a new grammar, but that I may read the great book that is written in that tongue. On January 24, 1835, Emerson wrote a letter to Lydia Jackson proposing marriage. Her acceptance reached him by mail on the 28th. In July 1835, he bought a house on the Cambridge and Concord Turnpike in Concord, Massachusetts which he named "Bush"; it is now open to the public as the Ralph Waldo Emerson House. Emerson quickly became one of the leading citizens in the town. He gave a lecture to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the town of Concord on September 12, 1835. Two days later, he married Lydia Jackson in her home town of Plymouth, Massachusetts, and moved to the new home in Concord together with Emerson's mother on September 15. Emerson quickly changed his wife's name to Lidian, and would call her Queenie, and sometimes Asia, and she called him Mr. Emerson. Their children were Waldo, Ellen, Edith, and Edward Waldo Emerson. Ellen was named for his first wife, at Lidian's suggestion. Emerson was poor when he was at Harvard, and later supported his family for much of his life. He inherited a fair amount of money after his first wife's death, though he had to file a lawsuit against the Tucker family in 1836 to get it. He received $11, in May 1834, and a further $11,. in July 1837. In 1834, he considered that he had an income of $1, a year from the initial payment of the estate, equivalent to what he had earned as a pastor. Literary career and Transcendentalism On September 8, 1836, the day before the publication of Nature, Emerson met with Henry Hedge, George Putnam and George Ripley to plan periodic gatherings of other like-minded intellectuals. This was the beginning of the Transcendental Club, which served as a center for the movement. Its first official meeting was held on September 19, 1836. On September 1, 1837, women attended a meeting of the Transcendental Club for the first time. Emerson invited Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Hoar and Sarah Ripley for dinner at his home before the meeting to ensure that they would be present for the evening get-together. Fuller would prove to be an important figure in Transcendentalism. Emerson anonymously published his first essay, Nature, on September 9, 1836. A year later, on August 31, 1837, Emerson delivered his now-famous Phi Beta Kappa address, "The American Scholar", then known as "An Oration, Delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Cambridge"; it was renamed for a collection of essays (which included the first general publication of "Nature") in 1849. Friends urged him to publish the talk, and he did so, at his own expense, in an edition of 500 copies, which sold out in a month. In the speech, Emerson declared literary independence in the United States and urged Americans to create a writing style all their own and free from Europe. James Russell Lowell, who was a student at Harvard at the time, called it "an event without former parallel on our literary annals". Another member of the audience, Reverend John Pierce, called it "an apparently incoherent and unintelligible address". In 1837, Emerson befriended Henry David Thoreau. Though they had likely met as early as 1835, in the fall of 1837, Emerson asked Thoreau, "Do you keep a journal?" The question went on to have a lifelong inspiration for Thoreau. Emerson's own journal comes to 16 large volumes, in the definitive Harvard University Press edition published between 1960 and 1982. Some scholars consider the journal to be Emerson's key literary work. In March 1837, Emerson gave a series of lectures on The Philosophy of History at Boston's Masonic Temple. This was the first time he managed a lecture series on his own, and was the beginning of his serious career as a lecturer. The profits from this series of lectures were much larger than when he was paid by an organization to talk, and Emerson continued to manage his own lectures often throughout his lifetime. He would eventually give as many as 80 lectures a year, traveling across the northern part of the United States. He traveled as far as St. Louis, Des Moines, Minneapolis, and California. On July 15, 1838, Emerson was invited to Divinity Hall, Harvard Divinity School for the school's graduation address, which came to be known as his "Divinity School Address". Emerson discounted Biblical miracles and proclaimed that, while Jesus was a great man, he was not God: historical Christianity, he said, had turned Jesus into a "demigod, as the Orientals or the Greeks would describe Osiris or Apollo". His comments outraged the establishment and the general Protestant community. For this, he was denounced as an atheist, and a poisoner of young men's minds. Despite the roar of critics, he made no reply, leaving others to put forward a defense. He was not invited back to speak at Harvard for another thirty years. The Transcendental group began to publish its flagship journal, The Dial, in July 1840. They planned the journal as early as October 1839, but work did not begin until the first week of 1840. George Ripley was its managing editor and Margaret Fuller was its first editor, having been hand-chosen by Emerson after several others had declined the role. Fuller stayed on for about two years and Emerson took over, utilizing the journal to promote talented young writers including Ellery Channing and Thoreau. It was in 1841 that Emerson published Essays, his second book, which included the famous essay, "Self-Reliance". His aunt called it a "strange medley of atheism and false independence", but it gained favorable reviews in London and Paris. This book, and its popular reception, more than any of Emerson's contributions to date laid the groundwork for his international fame. In January 1842 Emerson's first son Waldo died from scarlet fever. Emerson wrote of his grief in the poem "Threnody" ("For this losing is true dying"), and the essay "Experience". That same month, William James was born, and Emerson agreed to be his godfather. Bronson Alcott announced his plans in November 1842 to find "a farm of a hundred acres in excellent condition with good buildings, a good orchard and grounds". Charles Lane purchased a 90-acre (360, m2) farm in Harvard, Massachusetts, in May 1843 for what would become Fruitlands, a community based on Utopian ideals inspired in part by Transcendentalism. The farm would run based on a communal effort, using no animals for labor; its participants would eat no meat and use no wool or leather. Emerson said he felt "sad at heart" for not engaging in the experiment himself. Even so, he did not feel Fruitlands would be a success. "Their whole doctrine is spiritual", he wrote, "but they always end with saying, Give us much land and money". Even Alcott admitted he was not prepared for the difficulty in operating Fruitlands. "None of us were prepared to actualize practically the ideal life of which we dreamed. So we fell apart", he wrote. After its failure, Emerson helped buy a farm for Alcott's family in Concord which Alcott named "Hillside". The Dial ceased publication in April 1844; Horace Greeley reported it as an end to the "most original and thoughtful periodical ever published in this country". (An unrelated magazine of the same name would be published in several periods through 1929.) In 1844, Emerson published his second collection of essays, entitled "Essays: Second Series." This collection included "The Poet," "Experience," "Gifts," and an essay entitled "Nature," a different work from the 1836 essay of the same name. Emerson made a living as a popular lecturer in New England and much of the rest of the country. He had begun lecturing in 1833; by the 1850s he was giving as many as 80 per year. He addressed the Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge and the Gloucester Lyceum, among others. Emerson spoke on a wide variety of subjects and many of his essays grew out of his lectures. He charged between $10 and $50 for each appearance, bringing him as much as $2, in a typical winter "season". This was more than his earnings from other sources. In some years, he earned as much as $900 for a series of six lectures, and in another, for a winter series of talks in Boston, he netted $1,. He eventually gave some 1, lectures in his lifetime. His earnings allowed him to expand his property, buying 11 acres (45, m2) of land by Walden Pond and a few more acres in a neighboring pine grove. He wrote that he was "landlord and waterlord of 14 acres, more or less". Emerson was introduced to Indian philosophy when reading the works of French philosopher Victor Cousin. In 1845, Emerson's journals show he was reading the Bhagavad Gita and Henry Thomas Colebrooke's Essays on the Vedas. Emerson was strongly influenced by the Vedas, and much of his writing has strong shades of nondualism. One of the clearest examples of this can be found in his essay "The Over-soul”: We live in succession, in division, in parts, in particles. Meantime within man is the soul of the whole; the wise silence; the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related, the eternal ONE. And this deep power in which we exist and whose beatitude is all accessible to us, is not only self-sufficing and perfect in every hour, but the act of seeing and the thing seen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject and the object, are one. We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree; but the whole, of which these are shining parts, is the soul. From 1847 to 1848, he toured England, Scotland, and Ireland. He also visited Paris between the February Revolution and the bloody June Days. When he arrived, he saw the stumps where trees had been cut down to form barricades in the February riots. On May 21 he stood on the Champ de Mars in the midst of mass celebrations for concord, peace and labor. He wrote in his journal: "At the end of the year we shall take account, & see if the Revolution was worth the trees." In February 1852 Emerson and James Freeman Clarke and William Henry Channing edited an edition of the works and letters of Margaret Fuller, who had died in 1850. Within a week of her death, her New York editor Horace Greeley suggested to Emerson that a biography of Fuller, to be called Margaret and Her Friends, be prepared quickly "before the interest excited by her sad decease has passed away". Published with the title The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli, Fuller's words were heavily censored or rewritten. The three editors were not concerned about accuracy; they believed public interest in Fuller was temporary and that she would not survive as a historical figure. Even so, for a time, it was the best-selling biography of the decade and went through thirteen editions before the end of the century. Walt Whitman published the innovative poetry collection Leaves of Grass in 1855 and sent a copy to Emerson for his opinion. Emerson responded positively, sending a flattering five-page letter as a response. Emerson's approval helped the first edition of Leaves of Grass stir up significant interest and convinced Whitman to issue a second edition shortly thereafter. This edition quoted a phrase from Emerson's letter, printed in gold leaf on the cover: "I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career". Emerson took offense that this letter was made public and later became more critical of the work. Civil War years Emerson was staunchly anti-slavery, but he did not appreciate being in the public limelight and was hesitant about lecturing on the subject. He did, however, give a number of lectures during the pre-Civil War years, beginning as early as November, 1837. A number of his friends and family members were more active abolitionists than he, at first, but from 1844 on, he took a more active role in opposing slavery. He gave a number of speeches and lectures, and notably welcomed John Brown to his home during Brown's visits to Concord. He voted for Abraham Lincoln in 1860, but Emerson was disappointed that Lincoln was more concerned about preserving the Union than eliminating slavery outright. Once the American Civil War broke out, Emerson made it clear that he believed in immediate emancipation of the slaves. Around this time, in 1860, Emerson published The Conduct of Life, his final original collection of essays. In this book, Emerson "grappled with some of the thorniest issues of the moment," and "his experience in the abolition ranks is a telling influence in his conclusions. In the book's opening essay, Fate, Emerson wrote, "The question of the times resolved itself into a practical question of the conduct of life. How shall I live?" Emerson visited Washington, D.C, at the end of January, 1862. He gave a public lecture at the Smithsonian on January 31, 1862, and declared: "The South calls slavery an institution... I call it destitution... Emancipation is the demand of civilization". The next day, February 1, his friend Charles Sumner took him to meet Lincoln at the White House. Lincoln was familiar with Emerson's work, having previously seen him lecture. Emerson's misgivings about Lincoln began to soften after this meeting. In 1865, he spoke at a memorial service held for Lincoln in Concord: "Old as history is, and manifold as are its tragedies, I doubt if any death has caused so much pain as this has caused, or will have caused, on its announcement." Emerson also met a number of high-ranking government officials, including Salmon P. Chase, the secretary of the treasury, Edward Bates, the attorney general, Edwin M. Stanton, the secretary of war, Gideon Welles, the secretary of the navy, and William Seward, the secretary of state. On May 6, 1862, Emerson's protégé Henry David Thoreau died of tuberculosis at the age of 44 and Emerson delivered his eulogy. Emerson would continuously refer to Thoreau as his best friend, despite a falling out that began in 1849 after Thoreau published A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Another friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne, died two years after Thoreau in 1864. Emerson served as one of the pallbearers as Hawthorne was buried in Concord, as Emerson wrote, "in a pomp of sunshine and verdure". He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1864. Final years and death Starting in 1867, Emerson's health began declining; he wrote much less in his journals. Beginning as early as the summer of 1871 or in the spring of 1872, Emerson started having memory problems and suffered from aphasia. By the end of the decade, he forgot his own name at times and, when anyone asked how he felt, he responded, "Quite well; I have lost my mental faculties, but am perfectly well". Emerson's Concord home caught fire on July 24, 1872; Emerson called for help from neighbors and, giving up on putting out the flames, all attempted to save as many objects as possible. The fire was put out by Ephraim Bull, Jr., the one-armed son of Ephraim Wales Bull. Donations were collected by friends to help the Emersons rebuild, including $5, gathered by Francis Cabot Lowell, another $10, collected by LeBaron Russell Briggs, and a personal donation of $1, from George Bancroft. Support for shelter was offered as well; though the Emersons ended up staying with family at the Old Manse, invitations came from Anne Lynch Botta, James Elliot Cabot, James Thomas Fields and Annie Adams Fields. The fire marked an end to Emerson's serious lecturing career; from then on, he would lecture only on special occasions and only in front of familiar audiences. While the house was being rebuilt, Emerson took a trip to England, continental Europe, and Egypt. He left on October 23, 1872, along with his daughter Ellen while his wife Lidian spent time at the Old Manse and with friends. Emerson and his daughter Ellen returned to the United States on the ship Olympus along with friend Charles Eliot Norton on April 15, 1873. Emerson's return to Concord was celebrated by the town and school was canceled that day. In late 1874 Emerson published an anthology of poetry called Parnassus, which included poems by Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Julia Caroline Dorr, Jean Ingelow, Lucy Larcom, Jones Very, as well as Thoreau and several others. The anthology was originally prepared as early as the fall of 1871 but was delayed when the publishers asked for revisions. The problems with his memory had become embarrassing to Emerson and he ceased his public appearances by 1879. As Holmes wrote, "Emerson is afraid to trust himself in society much, on account of the failure of his memory and the great difficulty he finds in getting the words he wants. It is painful to witness his embarrassment at times". On April 21, 1882, Emerson was diagnosed with pneumonia. He died on April 27, 1882. Emerson is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts. He was placed in his coffin wearing a white robe given by American sculptor Daniel Chester French. Lifestyle and beliefs Emerson's religious views were often considered radical at the time. He believed that all things are connected to God and, therefore, all things are divine. Critics believed that Emerson was removing the central God figure; as Henry Ware, Jr. said, Emerson was in danger of taking away "the Father of the Universe" and leaving "but a company of children in an orphan asylum". Emerson was partly influenced by German philosophy and Biblical criticism. His views, the basis of Transcendentalism, suggested that God does not have to reveal the truth but that the truth could be intuitively experienced directly from nature. Emerson did not become an ardent abolitionist until 1844, though his journals show he was concerned with slavery beginning in his youth, even dreaming about helping to free slaves. In June 1856, shortly after Charles Sumner, a United States Senator, was beaten for his staunch abolitionist views, Emerson lamented that he himself was not as committed to the cause. He wrote, "There are men who as soon as they are born take a bee-line to the axe of the inquisitor... Wonderful the way in which we are saved by this unfailing supply of the moral element". After Sumner's attack, Emerson began to speak out about slavery. "I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom", he said at a meeting at Concord that summer. Emerson used slavery as an example of a human injustice, especially in his role as a minister. In early 1838, provoked by the murder of an abolitionist publisher from Alton, Illinois named Elijah Parish Lovejoy, Emerson gave his first public antislavery address. As he said, "It is but the other day that the brave Lovejoy gave his breast to the bullets of a mob, for the rights of free speech and opinion, and died when it was better not to live". John Quincy Adams said the mob-murder of Lovejoy "sent a shock as of any earthquake throughout this continent". However, Emerson maintained that reform would be achieved through moral agreement rather than by militant action. By August 1, 1844, at a lecture in Concord, he stated more clearly his support for the abolitionist movement. He stated, "We are indebted mainly to this movement, and to the continuers of it, for the popular discussion of every point of practical ethics". Emerson may have had erotic thoughts about at least one man. During his early years at Harvard, he found himself attracted to a young freshman named Martin Gay about whom he wrote sexually charged poetry. He also had a number of crushes on various women throughout his life, such as Anna Barker and Caroline Sturgis. Legacy As a lecturer and orator, Emerson—nicknamed the Concord Sage—became the leading voice of intellectual culture in the United States. Herman Melville, who had met Emerson in 1849, originally thought he had "a defect in the region of the heart" and a "self-conceit so intensely intellectual that at first one hesitates to call it by its right name", though he later admitted Emerson was "a great man". Theodore Parker, a minister and Transcendentalist, noted Emerson's ability to influence and inspire others: "the brilliant genius of Emerson rose in the winter nights, and hung over Boston, drawing the eyes of ingenuous young people to look up to that great new start, a beauty and a mystery, which charmed for the moment, while it gave also perennial inspiration, as it led them forward along new paths, and towards new hopes". Emerson's work not only influenced his contemporaries, such as Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau, but would continue to influence thinkers and writers in the United States and around the world down to the present. Notable thinkers who recognize Emerson's influence include Nietzsche and William James, Emerson's godson. "There is little disagreement that Emerson was the most influential writer of 19th-century America, though these days he is largely the concern of scholars. Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau and William James were all positive Emersonians, while Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry James were Emersonians in denial — while they set themselves in opposition to the sage, there was no escaping his influence. To T. S. Eliot, Emerson’s essays were an “encumbrance.” Waldo the Sage was eclipsed from 1914 until 1965, when he returned to shine, after surviving in the work of major American poets like Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens and Hart Crane." In his book The American Religion, Harold Bloom repeatedly refers to Emerson as "The prophet of the American Religion," which in the context of the book refers to indigenously American religions such as Mormonism and Christian Science, which arose largely in Emerson's lifetime, but also to Mainline Protestant churches that Bloom says have become in the United States more gnostic than their European counterparts. In The Western Canon, Harold Bloom compares Emerson to Michel de Montaigne: "The only equivalent reading experience that I know is to reread endlessly in the notebooks and journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the American version of Montaigne." Several of Emerson's poems were included in Bloom's The Best Poems of the English Language, although he wrote that none of the poems are as outstanding as the best of Emerson's essays, which Bloom listed as Self-Reliance, Circles, Experience, and "nearly all of Conduct of Life”. Namesakes * In May 2006, 168 years after Emerson delivered his "Divinity School Address," Harvard Divinity School announced the establishment of the Emerson Unitarian Universalist Association Professorship. Harvard has also named a building, Emerson Hall (1900), after him. * Emerson Hill, a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Staten Island, is named for his eldest brother, Judge William Emerson, who resided there from 1837 to 1864. * The Emerson String Quartet, formed in 1976, took their name from Ralph Waldo Emerson. * The Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize is awarded annually to high school students for essays on historical subjects. * Author Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1914 – April 16, 1994) was named after Emerson. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Waldo_Emerson

Oliver Wendell Holmes (August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most famous prose works are the "Breakfast-Table" series, which began with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858). He was also an important medical reformer. In addition to his work as an author and poet, Holmes also served as a physician, professor, lecturer, inventor, and, although he never practiced it, he received formal training in law.

John Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887 – January 20, 1962) was an American poet, known for his work about the central California coast. Much of Jeffers' poetry was written in narrative and epic form, but he is also known for his shorter verse and is considered an icon of the environmental movement. Influential and highly regarded in some circles, despite or because of his philosophy of "inhumanism," Jeffers believed that transcending conflict required human concerns to be de-emphasized in favor of the boundless whole. This led him to oppose U.S. participation in World War II, a stand that was controversial at the time. Jeffers was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), the son of a Presbyterian minister and biblical scholar, Reverend Dr. William Hamilton Jeffers, and Annie Robinson Tuttle. His brother was Hamilton Jeffers, who became a well-known astronomer, working at Lick Observatory. His family was supportive of his interest in poetry. He traveled through Europe during his youth and attended school in Switzerland. He was a child prodigy, interested in classics and Greek and Latin language and literature. At sixteen he entered Occidental College. At school, he was an avid outdoorsman, and active in the school's literary societies. After he graduated from Occidental, Jeffers went to the University of Southern California to study at first literature, and then medicine. He met Una Call Kuster in 1906; she was three years older than he was, a graduate student, and the wife of a Los Angeles attorney. In 1910 he enrolled as a forestry student at the University of Washington in Seattle, a course of study that he abandoned after less than one year, at which time he returned to Los Angeles. Sometime before this, he and Una had begun an affair that became a scandal, reaching the front page of the Los Angeles Times in 1912. After Una spent some time in Europe to quiet things down, the two were married in 1913, and moved to Carmel, California, where Jeffers constructed Tor House and Hawk Tower. The couple had a daughter who died a day after birth in 1914, and then twin sons (Donnan and Garth) in 1916. Una died of cancer in 1950. Jeffers died in 1962; an obituary can be found in the New York Times, January 22, 1962. Poetic career In the 1920s and 1930s, at the height of his popularity, Jeffers was famous for being a tough outdoorsman, living in relative solitude and writing of the difficulty and beauty of the wild. He spent most of his life in Carmel, California, in a granite house that he had built himself called "Tor House and Hawk Tower". Tor is a term for a craggy outcrop or lookout. Before Jeffers and Una purchased the land where Tor House would be built, they rented two cottages in Carmel, and enjoyed many afternoon walks and picnics at the "tors" near the site that would become Tor House. To build the first part of Tor House, a small, two story cottage, Jeffers hired a local builder, Michael Murphy. He worked with Murphy, and in this short, informal apprenticeship, he learned the art of stonemasonry. He continued adding on to Tor House throughout his life, writing in the mornings and working on the house in the afternoon. Many of his poems reflect the influence of stone and building on his life. He later built a large four-story stone tower on the site called Hawk Tower. While he had not visited Ireland at this point in his life, it is possible that Hawk Tower is based on Francis Joseph Bigger's 'Castle Séan' at Ardglass, County Down, which had also in turn influenced Yeats' poets tower, Thoor Ballylee. Construction on Tor House continued into the late 1950s and early 1960s, and was completed by his eldest son. The completed residence was used as a family home until his descendants decided to turn it over to the Tor House Foundation, formed by Ansel Adams, for historic preservation. The romantic Gothic tower was named after a hawk that appeared while Jeffers was working on the structure, and which disappeared the day it was completed. The tower was a gift for his wife Una, who had a fascination for Irish literature and stone towers. In Una's special room on the second floor were kept many of her favorite items, photographs of Jeffers taken by the artist Weston, plants and dried flowers from Shelley's grave, and a rosewood melodeon which she loved to play. The tower also included a secret interior staircase – a source of great fun for his young sons. During this time, Jeffers published volumes of long narrative blank verse that shook up the national literary scene. These poems, including Tamar and Roan Stallion, introduced Jeffers as a master of the epic form, reminiscent of ancient Greek poets. These poems were full of controversial subject matter such as incest, murder and parricide. Jeffers' short verse includes "Hurt Hawks," "The Purse-Seine" and "Shine, Perishing Republic." His intense relationship with the physical world is described in often brutal and apocalyptic verse, and demonstrates a preference for the natural world over what he sees as the negative influence of civilization. Jeffers did not accept the idea that meter is a fundamental part of poetry, and, like Marianne Moore, claimed his verse was not composed in meter, but "rolling stresses." He believed meter was imposed on poetry by man and not a fundamental part of its nature. nitially, Tamar and Other Poems received no acclaim, but when East Coast reviewers discovered the work and began to compare Jeffers to Greek tragedians, Boni & Liveright reissued an expanded edition as Roan Stallion, Tamar and Other Poems (1925). In these works, Jeffers began to articulate themes that contributed to what he later identified as Inhumanism. Mankind was too self-centered, he complained, and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." Jeffers's longest and most ambitious narrative, The Women at Point Sur (1927), startled many of his readers, heavily loaded as it was with Nietzschean philosophy. The balance of the 1920s and the early 1930s were especially productive for Jeffers, and his reputation was secure. In 1934, he made the acquaintance of the philosopher J Krishnamurti and was struck by the force of Krishnamurti's person. He wrote a poem entitled "Credo" which many feel refers to Krishnamurti. In Cawdor and Other Poems (1928), Dear Judas and Other Poems (1929), Descent to the Dead, Poems Written in Ireland and Great Britain (1931), Thurso's Landing (1932), and Give Your Heart to the Hawks (1933), Jeffers continued to explore the questions of how human beings could find their proper relationship (free of human egocentrism) with the divinity of the beauty of things. These poems, set in the Big Sur region (except Dear Judas and Descent to the Dead), enabled Jeffers to pursue his belief that the natural splendor of the area demanded tragedy: the greater the beauty, the greater the demand. As Euripides had, Jeffers began to focus more on his own characters' psychologies and on social realities than on the mythic. The human dilemmas of Phaedra, Hippolytus, and Medea fascinated him. Many books followed Jeffers' initial success with the epic form, including an adaptation of Euripides' Medea, which became a hit Broadway play starring Dame Judith Anderson. D. H. Lawrence, Edgar Lee Masters, Benjamin De Casseres, and George Sterling were close friends of Jeffers, Sterling having the longest and most intimate relationship with him. While living in Carmel, Jeffers became the focal point for a small but devoted group of admirers. At the peak of his fame, he was one of the few poets to be featured on the cover of Time Magazine. He was also asked to read at the Library of Congress, and was posthumously put on a U.S. postage stamp. Part of the decline of Jeffers' popularity was due to his staunch opposition to the United States' entering World War II. In fact, his book The Double Axe and Other Poems (1948), a volume of poems that was largely critical of U.S. policy, came with an extremely unconventional note from Random House that the views expressed by Jeffers were not those of the publishing company. Soon after, his work was received negatively by several influential literary critics. Several particularly scathing pieces were penned by Yvor Winters, as well as by Kenneth Rexroth, who had been very positive in his earlier commentary on Jeffers' work. Jeffers would publish poetry intermittently during the 1950s but his poetry never again attained the same degree of popularity that it had in the 1920s and the 1930s. Inhumanism Jeffers coined the word inhumanism, the belief that mankind is too self-centered and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things." In the famous poem "Carmel Point," Jeffers called on humans to "uncenter" themselves. In "The Double Axe," Jeffers explicitly described inhumanism as "a shifting of emphasis and significance from man to notman; the rejection of human solipsism and recognition of the trans-human magnificence. ... This manner of thought and feeling is neither misanthropic nor pessimist. ... It offers a reasonable detachment as rule of conduct, instead of love, hate and envy ... it provides magnificence for the religious instinct, and satisfies our need to admire greatness and rejoice in beauty." In The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers,the first in-depth study of Jeffers not written by one of his circle, poet and critic J. Radcliffe Squires addresses the question of a reconciliation of the beauty of the world and potential beauty in mankind: “Jeffers has asked us to look squarely at the universe. He has told us that materialism has its message, its relevance, and its solace. These are different from the message, relevance, and solace of humanism. Humanism teaches us best why we suffer, but materialism teaches us how to suffer.” Influence His poems have been translated into many languages and published all over the world. Outside of the United States he is most popular in Japan and the Czech Republic. William Everson, Edward Abbey, Gary Snyder, and Mark Jarman are just a few recent authors who have been influenced by Jeffers. Charles Bukowski remarked that Jeffers was his favorite poet. Polish poet Czesław Miłosz also took an interest in Jeffers' poetry and worked as a translator for several volumes of his poems. Jeffers also exchanged some letters with his Czech translator and popularizer, the poet Kamil Bednář. Writer Paul Mooney (1904–1939), son of American Indian authority James Mooney (1861–1921) and collaborator of travel writer Richard Halliburton (1900–1939), "was known always to carry with him (a volume of Jeffers) as a chewer might carry a pouch of tobacco ... and, like Jeffers," writes Gerry Max in Horizon Chasers, "worshipped nature ... (taking) refuge (from the encroachments of civilization) in a sort of chthonian mysticism rife with Greek dramatic elements ..." Jeffers was an inspiration and friend to western U.S. photographers of the early twentieth century, including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Morley Baer. In fact, the elegant book of Baer's photographs juxtaposed with Jeffers' poetry, combines the creative talents of those two residents of the Big Sur coast. Although Jeffers has largely been marginalized in the mainstream academic community over the last thirty years, several important contemporary literary critics, including Albert Gelpi of Stanford University, and poet, critic and NEA chairman Dana Gioia, have consistently cited Jeffers as a formidable presence in modern literature. His poem "The Beaks of Eagles" was made into a song by The Beach Boys on their album Holland (1973). Two lines from Jeffers' poem "We Are Those People" are quoted toward the end of the 2008 film Visioneers. Several lines from Jeffers' poem "Wise Men in Their Bad Hours" ("Death's a fierce meadowlark: but to die having made / Something more equal to the centuries / Than muscle and bone, is mostly to shed weakness.") appear in Christopher McCandless' diary. Robinson Jeffers is mentioned in the 2004 film I Heart Huckabees by the character Albert Markovski played by Jason Schwartzman, when defending Jeffers as a nature writer against another character's claim that environmentalism is socialism. Markovski says, "Henry David Thoreau, Robinson Jeffers, the National Geographic Society...all socialists?" Further reading and research The largest collections of Jeffers' manuscripts and materials are in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin and in the libraries at Occidental College, the University of California, and Yale University. A collection of his letters has been published as The Selected Letters of Robinson Jeffers, 1887–1962 (1968). Other books of criticism and poetry by Jeffers are: Poetry, Gongorism and a Thousand Years (1949), Themes in My Poems (1956), Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems (1965), The Alpine Christ and Other Poems (1974), What Odd Expedients" and Other Poems (1981), and Rock and Hawk: A Selection of Shorter Poems by Robinson Jeffers (1987). Stanford University Press recently released a five-volume collection of the complete works of Robinson Jeffers. In an article titled, "A Black Sheep Joins the Fold", written upon the release of the collection in 2001, Stanford Magazine commented that it was remarkable that, due to a number of circumstances, "there was never an authoritative, scholarly edition of California’s premier bard" until the complete works published by Stanford. Biographical studies include George Sterling, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and the Artist (1926); Louis Adamic, Robinson Jeffers (1929); Melba Bennett, Robinson Jeffers and the Sea (1936) and The Stone Mason of Tor House (1966); Radcliffe Squires, The Loyalties of Robinson Jeffers (1956); Edith Greenan, Of Una Jeffers (1939); Mabel Dodge Luhan, Una and Robin (1976; written in 1933); Ward Ritchie, Jeffers: Some Recollections of Robinson Jeffers (1977); and James Karman, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of California (1987). Books about Jeffers's career include L. C. Powell, Robinson Jeffers: The Man and His Work (1940; repr. 1973); William Everson, Robinson Jeffers: Fragments of an Older Fury (1968); Arthur B. Coffin, Robinson Jeffers: Poet of Inhumanism (1971); Bill Hotchkiss, Jeffers: The Sivaistic Vision (1975); James Karman, ed., Critical Essays on Robinson Jeffers (1990); Alex Vardamis The Critical Reputation of Robinson Jeffers (1972); and Robert Zaller, ed., Centennial Essays for Robinson Jeffers (1991). The Robinson Jeffers Newsletter, ed. Robert Brophy, is a valuable scholarly resource. In a rare recording, Jeffers can be heard reading his "The Day Is A Poem" (September 19, 1939) on Poetry Speaks – Hear Great Poets Read Their Work from Tennyson to Plath, Narrated by Charles Osgood (Sourcebooks, Inc., c2001), Disc 1, #41; including text, with Robert Hass on Robinson Jeffers, pp. 88–95. Jeffers was also on the cover of Time – The Weekly Magazine, April 4, 1932 (pictured on p. 90. Poetry Speaks). Jeffers Studies, a journal of research on the poetry of Robinson Jeffers and related topics, is published semi-annually by the Robinson Jeffers Association. Bibliography * Flagons and Apples. Los Angeles: Grafton, 1912. * Californians. New York: Macmillan, 1916. * Tamar and Other Poems. New York: Peter G. Boyle, 1924. * Roan Stallion, Tamar, and Other Poems. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1925. * The Women at Point Sur. New York: Liveright, 1927. * Cawdor and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1928. * Dear Judas and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1929. * Thurso's Landing and Other Poems. New York: Liveright, 1932. * Give Your Heart to the Hawks and other Poems. New York: Random House, 1933. * Solstice and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1935. * Such Counsels You Gave To Me and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1937. * The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. New York: Random House, 1938. * Be Angry at the Sun. New York: Random House, 1941. * Medea. New York: Random House, 1946. * The Double Axe and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1948. * Hungerfield and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1954. * The Beginning and the End and Other Poems. New York: Random House, 1963. * Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems. New York: Vintage, 1965. * Stones of the Sur. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robinson_Jeffers