Info

Toile double tissée oiseau

William Morris

1878

William Morris Gallery

Edward Dowden (/ˈdaʊdən/; 3 May 1843– 4 April 1913), was an Irish critic and poet. Biography He was the son of John Wheeler Dowden, a merchant and landowner, and was born at Cork, three years after his brother John, who became Bishop of Edinburgh in 1886. Edward’s literary tastes emerged early, in a series of essays written at the age of twelve. His home education continued at Queen’s College, Cork and at Trinity College, Dublin; at the latter he had a distinguished career, becoming president of the Philosophical Society, and winning the vice-chancellor’s prize for English verse and prose, and the first senior moderatorship in ethics and logic. In 1867 he was elected professor of oratory and English literature in Dublin University. Dowden’s first book, Shakespeare, his Mind and Art (1875), resulted from a revision of a course of lectures, and made him widely known as a critic: translations appeared in German and Russian; his Poems (1876) went into a second edition. His Shakespeare Primer (1877) was translated into Italian and German. In 1878 the Royal Irish Academy awarded him the Cunningham gold medal “for his literary writings, especially in the field of Shakespearian criticism.” Later works by him in this field included an edition of The Sonnets of William Shakespeare (1881), Passionate Pilgrim (1883), Introduction to Shakespeare (1893), Hamlet (1899), Romeo and Juliet (1900), Cymbeline (1903), and an article entitled “Shakespeare as a Man of Science” (in the National Review, July 1902), which criticized T.E. Webb’s Mystery of William Shakespeare. His critical essays “Studies in Literature” (1878), “Transcripts and Studies” (1888), “New Studies in Literature” (1895) showed a profound knowledge of the currents and tendencies of thought in various ages and countries; but his Life of Shelley (1886) made him best known to the public at large. In 1900 he edited an edition of Shelley’s works. Other books by him which indicate his interests in literature include: Robert Southey (in the “English Men of Letters” series, 1880), his edition of Southey’s Correspondence with Caroline Bowles (1881), and Select Poems of Southey (1895), his Correspondence of Sir Henry Taylor (1888), his edition of Wordsworth’s Poetical Works (1892) and of his Lyrical Ballads (1890), his French Revolution and English Literature (1897; lectures given at Princeton University in 1896), History of French Literature (1897), Puritan and Anglican (1900), Robert Browning (1904) and Michel de Montaigne (1905). His devotion to Goethe led to his succeeding Max Müller in 1888 as president of the English Goethe Society. In 1889 he gave the first annual Taylorian Lecture at the University of Oxford, and from 1892 to 1896 served as Clark lecturer at Trinity College, Cambridge. To his research are due, among other matters of literary interest, the first account of Thomas Carlyle’s Lectures on periods of European culture; the identification of Shelley as the author of a review (in The Critical Review of December 1814) of a lost romance by James Hogg; a description of Shelley’s Philosophical View of Reform; a manuscript diary of Fabre d’Églantine; and a record by Dr Wilhelm Weissenborn of Goethe’s last days and death. He also discovered a Narrative of a Prisoner of War under Napoleon (published in Blackwood’s Magazine), an unknown pamphlet by Bishop Berkeley, some unpublished writings of William Hayley relating to Cowper, and a unique copy of the Tales of Terror. His wide interests and scholarly methods made his influence on criticism both sound and stimulating, and his own ideals are well described in his essay on The Interpretation of Literature in his Transcripts and Studies. As commissioner of education in Ireland (1896–1901), trustee of the National Library of Ireland, secretary of the Irish Liberal Union and vice-president of the Irish Unionist Alliance, he enforced his view that literature should not be divorced from practical life. His biographical/critical concepts, particularly in connection with Shakespeare, are played with by Stephen Dedalus in the library chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Leslie Fiedler was to play with them again in The Stranger in Shakespeare. Dowden married twice, first (1866) Mary Clerke, and secondly (1895) Elizabeth Dickinson West, daughter of the dean of St Patrick’s. His daughter by his first wife, Hester Dowden, was a well-known spiritualist medium. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Dowden

William Craig Berkson (August 30, 1939– June 16, 2016) was an American poet, critic, and teacher who was active in the art and literary worlds from his early twenties on. Early life and education Born in New York City on August 30, 1939, Bill Berkson grew up on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, the only child of Seymour Berkson, general manager of International News Service and later publisher of the New York Journal American, and the fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert. He attended The Day School of the Church of the Heavenly Rest and transferred to Trinity School in 1945. He graduated from Lawrenceville School in 1957. He dropped out of Brown University to return to New York after his father died. He studied poetry at The New School for Social Research with Kenneth Koch. He attended Columbia University and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. Having begun writing poetry at Lawrenceville, encouraged there by such teachers as John Silver and the eminent Emily Dickinson scholar, Thomas H. Johnson, he went on to study short story writing with John Hawkes and prosody with S. Foster Damon at Brown. But his full commitment to poetry was prompted under the tutelage of Kenneth Koch in spring, 1959 at the New School for Social Research. It was also through Koch that he was introduced to the poetry and arts community loosely termed the New York School, which in turn led to close friendships with Frank O’Hara and such senior artists as Philip Guston and Alex Katz, as well as with poets and artists of his own generation such as Ron Padgett, Joe Brainard, George Schneeman, Ted Berrigan, Anne Waldman, Jim Carroll and others. Career After leaving Columbia in 1960, Berkson started work as an editorial associate at ARTnews, where he continued for the next three years. During the remainder of the 1960s, he was a regular contributor to both ARTnews and Arts, guest editor at the Museum of Modern Art, an associate producer of a program on art for public television, and taught literature and writing workshops at the New School for Social Research and Yale University. After moving to Northern California in 1970, Berkson began editing and publishing a series of poetry books and magazines under the Big Sky imprint and taught regularly in the California Poets in the Schools program. In 1975 he married the artist Lynn O’Hare; their son Moses Edwin Clay Berkson was born in Bolinas, California, on January 23, 1976. He also has a daughter, Siobhan O’Hare Mora Lopez (b. 1969), and three grandchildren, Henry Berkson and Estella and Lourdes Mora Lopez. His friendships during his California years included those with; Joanne Kyger, Duncan McNaughton and Philip Whalen. Berkson is the author of some twenty collections and pamphlets of poetry—including most recently Portrait and Dream: New & Selected Poems and Expect Delays, both from Coffee House Press. His poems have also appeared in many magazines and anthologies and have been translated into French, Russian, Hungarian, Dutch, Czechoslovakian, Romanian, Italian, German and Spanish. Les Parties du Corps, a selection of his poetry translated into French, appeared from Joca Seria, Nantes, in 2011. Other recent books are What’s Your Idea of a Good Time?: Letters & Interviews 1977-1985 with Bernadette Mayer; BILL with drawings by Colter Jacobsen; Ted Berrigan with George Schneeman; Not an Exit with Léonie Guyer and Repeat After Me with John Zurier. Beside the aforementioned collaborations, he executed extensive projects with visual artists Philip Guston, Alex Katz, Joe Brainard, Lynn O’Hare and Greg Irons, as well as with the poets Frank O’Hara, Larry Fagin, Ron Padgett, Anne Waldman and Bernadette Mayer. In the mid-1980s, Berkson resumed writing art criticism on a regular basis, contributing monthly reviews and articles to Artforum from 1985 to 1991; he became a corresponding editor for Art in America in 1988 and contributing editor for artcritical.com and has also written frequently for such magazines as Aperture, Modern Painters, Art on Paper and others. In 1984, he began teaching art history and literature and organizing the public lectures program at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he also served as interim dean in 1990 and Director of Letters and Science from 1993 to 1998. He retired from SFAI in 2008 and later held the position of Professor Emeritus. During the same period, he was also on the visiting faculty of Naropa Institute, California College of Arts and Crafts and Mills College. Berkson continued until the end of his life to lecture widely in colleges and universities. He published three collections of art criticism, to date, the last being For the Ordinary Artist: Short Reviews, Occasional Pieces & More. As a sometime curator, he organized or co-curated such exhibitions as Ronald Bladen: Early and Late (SFMoMA), Albert York (Mills College), Why Painting I & II (Susan Cummins Gallery), Homage to George Herriman (Campbell-Thiebaud Gallery), Facing Eden: 100 years of Northern California Landscape Art (M.H. de Young Museum), George Schneeman (CUE Foundation), Gordon Cook: Out There (Nelson Gallery, University of California, Davis), George Schneeman in Italy (Instituto di Cultura Italiano, San Francisco), and, with Ron Padgett, A Painter and His Poets: The Art of George Schneeman (Poets House, New York). In 1998, he married the curator Constance Lewallen, with whom he lived in the Eureka Valley section of San Francisco. Berkson died of a heart attack in San Francisco on June 16, 2016 at the age of 76. Berkson’s archive of literary, artistic and other materials, including extensive correspondence and collaborations with O’Hara, Guston, Brainard, Mayer and others through the years is maintained in the Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut, Storrs. Bibliography * Poetry * Saturday Night: Poems 1960-61 (Tibor de Nagy, 1961; reprint, Sand Dollar, 1975) * Shining Leaves (Angel Hair, 1969) * Recent Visitors (with drawings by George Schneeman) (Angel Hair, 1973) * Enigma Variations (with drawings by Philip Guston) (Big Sky, 1975) * 100 Women (Simon & Schuchat, 1975) * Blue Is the Hero (Poems 1960-75) (L, 1976) * Red Devil (Smithereens Press, 1983) * Start Over (Tombouctou Books, 1983) * Lush Life (Z Press, 1984) * A Copy of the Catalogue (Labyrinth, Vienna, 1999) * Serenade (Poetry & Prose 1975-1989) (Zoland Books, 2000) * Fugue State (Zoland Books, 2001) * 25 Grand View (San Francisco Center for the Book, 2002) * Gloria (with etchings by Alex Katz) (Arion Press, 2005) * Parts of the Body: a 1970s/80s scrapbook (Fell Swoop, 2006) * Same Here, online chapbook (Big Bridge, 2006) * Our Friends Will Pass Among You Silently (The Owl Press, 2007) * Goods and Services (Blue Press, 2008) * Portrait and Dream: New & Selected Poems (Coffee House Press, 2009) * Lady Air (Perdika Press, 2010) * Parties du Corps, trans. Olivier Brossard, Vincent Broqua et alia (Joca Seria, Nantes, 2011) * Snippets (Omerta, 2014) * Expect Delays (Coffee House Press, 2014) * Invisible Oligarchs (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2016) * Collaborations * Recent Visitors with Joe Brainard (Boke Press, 1971) * Hymns of St. Bridget with Frank O’Hara (Adventures in Poetry, 1975) * Ants with drawings by Greg Irons (Arif, 1975) * Two Serious Poems & One Other with Larry Fagin (Big Sky, 1972) * Hymns of St. Bridget & Other Writings with Frank O’ Hara (The Owl Press, 2001) * The World of Leon with Ron Padgett, Larry Fagin, & Michael Brownstein (Big Sky, 1976) * BILL, with Colter Jacobsen (Gallery 16, 2008) * Ted Berrigan, with George Schneeman (Cuneiform Press. 2009) * Not an Exit, with Léonie Guyer (Jungle Garden Press, 2010) * Repeat After Me, with John Zurier (Gallery Paule Anglim, 2011) * Amsterdam Souvenirs, with Joanne Kyger (Blue Press, 2016) * Memoirs * Young Manhattan (w/ Anne Waldman) (Erudite Fangs, 1999) * The Far Flowered Shore: Japan 2006/2010 (Cuneiform Press, 2013) * Since When [memoirs, forthcoming] * Prose * What’ s Your Idea of a Good Time?: Letters & Interviews (w/ Bernadette Mayer) (Tuumba Press, 2006) * Criticism * The Sweet Singer of Modernism & Other Art Writings 1985-2003 (Qua Books, 2004) * Sudden Address: Selected Lectures 1981-2006 (Cuneiform Press, 2007) * For The Ordinary Artist: Short Reviews, Interviews, Occasional Pieces & More (BlazeVox, 2010) * "Hands On/Hands Off," in The Art of Collaboration, Cuneiform Press, 2015 * “New Energies: Philip Guston Among the Poets,” in Philip Guston/ Drawings for Poets (Sievekind Verlag, 2015) * “Empathy and Sculpture,” in Joel Shapiro (Craig Starr Gallery, 2014) * “Eclipse, the View from the Cave” in Larry Deyab, 2014 * “Canan Tolon’s Open Limits,” in Cana Tolon (Parasol Unit, London, 2013) * “Larry Thomas’s Natural Wonders,” in Larry Thomas (Sonoma Valley Art Museum, 2012) * “Piero, Guston and their Followers,” Philip Guston/ Roma: a symposium (New York Review of * Books, 2014) * “ The Elements of Drawing” in Wayne Thiebaud: Still-Life Drawings (Paul Thiebaud Gallery, 2010) * “ Dean Smith in Action,” Dean Smith, (Gallery Paule Anglim San Francisco) * “ Dewey Crumpler’ s Metamorphoses,” in Dewey Crumpler (California African American Museum, Los Angeles, 2008) * “ Seeing with Bechtle,” in Robert Bechtle/ Plein Air (Gallery Paule Anglim, 2007) * “ On Adelie Landis Bischoff” (Salander O’ Reilly, 2006) * “ Ultramodern Park,” in David Park: the 1930s and 40s, 2006 * “ Introduction,” in Jo Babcock, The Invented Camera, 2005 * “ A New Luminist,” in Tim Davis, Permanent Collection, 2005 * “ George’ s House of Mozart,” in Painter Among Poets: The Collaborative Art of George Schneeman (Granary books, 2004) * “ George Schneeman’ s Italian Hours,” CUE Art Foundation, 2003 * “ Without The Rose: Jay DeFeo & 16 Americans,” in Jay DeFeo & The Rose (University of California Press, 2003) * “ Pyramid and Shoe” (Guston and Comics) in Philip Guston (Thames & Hudson, 2003) * “ The Abstract Bischoff,” Salander-O’ Reilly, 2002 * “ DeKooning, With Attitude,” in Writers on Artists, Modern Painters, 2002 * “ Spellbound” (Vija Celmins), McKee Gallery, 2002 * “ Warhol’ s History Lesson,” John Berggruen, 2001 * “ Join the Aminals” (Tom Neely), Jernigan-Wicker, 2001 * “ What the Ground Looks Like” in Aerial Muse: the Art of Yvonne Jacquette, Hudson Hills / Stanford Art Museum, 2001 * “ The Searcher” in Elmer Bischoff, University of California Press, 2001 * “ Ceremonial Surfaces” in Celebrating Modern Art: The Anderson Collection, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2000 * “ Existing Light” in Henry Wessel, Bransten Gallery, 2000 * “Jackson Pollock: The Colored Paper Drawings”, Washburn, 2000 * “ The Portraitist” in Elaine de Kooning / Portraits, Salander O’ Reilly Gallery, New York, 1999 * “ Hung Liu, Action Painter,” in Hung Liu, Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco,1998 * “ Things in Place,” in Table Tops: Morandi to Mapplethorpe, California Center for the Arts, Escondido, CA, 1997 * “ Autograph Hounds,” in Hall of Fame of Halls of Fame, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, 1997 * Homage to George Herriman, Campbell-Thiebaud Gallery, 1997 * “ The Romance of the Rose,” in Jay DeFeo, Moore College of Art, 1996 * “ Changes like the Weather,” in Facing Eden, University of California Press, 1995 * “ The Ideal Reader,” in Philip Guston: Poem Pictures, Addison Gallery, 1994 * “ Poet and Painter Coda,” in Franz Kline, Tàpies Foundation/Tate Gallery, 1994 * “ Apparition as Knowledge” in Deborah Oropallo, Wirtz Gallery, 1993 * “ The Thiebaud Papers,” in Wayne Thiebaud: Vision and Revision, Fine Arts Museums, 1992 * “Air and Such” in Biotherm by Frank O’Hara, Arion Press, 1990 * Ronald Bladen: Early and Late, SFMOMA, 1991 * Editor * In Memory of My Feelings by Frank O’Hara (posthumous collection of poetry, illustrated by 30 American artists) (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1967; reprint 2005) * Best & Company, a one-shot anthology of art & literature, 1969 * Alex Katz (with Irving Sandler) (Praeger, 1971) * Big Sky magazine (12 issues) and books (20 volumes), 1971–78 * Homage to Frank O’Hara (ith/ Joe LeSueur) (Big Sky, 1978; reprint * Creative Arts, 1980; 3rd edition, Big Sky, 1988) * The World Record (with Bob Rosenthal), LP of poets’ readings, St. Marks Poetry Project, 1980. * Art Journal, Special de Kooning Issue (with Rackstraw Downes), 1989 * What’s With Modern Art? By Frank O’ Hara (Mike & Dale’ s Press, 1998) * Anthologies * The Young American Poets,10 American Poets, The Young American Writers, The World Anthology, An Anthology of New York Poets, Best & Company, On the Mesa, Calafia, One World Poetry, Another World, Poets & Painters, The Ear, Aerial, Broadway, Broadway 2, Hills/Talks, Wonders, Up Late: American Poetry Since 1970, Best Minds, Out of This World, Reading Jazz, A Norton Anthology of Postmodern American Poetry, American Poets Say Goodbye to the 20th Century, Euro-San Francisco Poetry Festival, The Blind See Only this World, The Angel Hair Anthology, Evidence of the Paranormal, Enough, The New York Poets II, Bay Area Poetics, Hom(m)age to Whitman, POEM, The i.e. Reader, Nuova Poesia Americana: New York, A Norton Anthology of Postmodern American Poetry, Second Edition. * 'Other * Recordings of poetry on Disconnected (Giorno Poetry Systems) and The World Record (St Marks Poetry Project); Daniel Kane, All Poets Welcome; and in the American Poetry Archive (San Francisco State University), PennSound (University of Pennsylvania) & elsewhere. * Poetry translated into French, Italian, Turkish, Spanish, German, Dutch, Romanian, Arabic, Czechoslovakian and Hungarian. * Art reviews & essays regularly contributed to ARTnews 1961-64; Arts 1964-66; Art in America 1980- ; Artforum 1985-1990; Modern Painters, 1998–2003; artcritical.com 2009. Awards * * Dylan Thomas Memorial Poetry Award, The New School for Social Research, 1959 * Poets Foundation Grant, 1968 * Yaddo Fellowship, 1968 * Creative Writing Fellowship in Poetry, National Endowment for the Arts, 1980 * Briarcombe Fellowship, 1983 * Marin Arts Council Poetry Award, 1987 * Artspace Award for New Writing in Art Criticism, 1990 * Visiting Artist/Scholar, American Academy in Rome, 1991 * Fund for Poetry Grant, 1994, 2001 * San Francisco Public Library Laureate, 2001 * Guest of Honor, Small Press Distribution Open House, 2004 * Paul Mellon Distinguished Fellow (lecture), Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, 2006 * “Goldie” for Literature, the San Francisco Bay Guardian, 2008 * Balcones Poetry Prize, Austin, Texas, 2010 * Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines (CCLM) grants for publishing, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1978 * Honorable Mention, Editor’s Fellowship, CCLM, 1979 * NEA, Small Press Publishing Grants, 1975, 1977 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Berkson

Stanley Jasspon Kunitz (July 29, 1905 – May 14, 2006) was an American poet. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress twice, first in 1974 and then again in 2000. Biography Kunitz was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, the youngest of three children, to Yetta Helen (née Jasspon) and Solomon Z. Kunitz, both of Jewish Russian Lithuanian descent.His father, a dressmaker of Russian Jewish heritage, committed suicide in a public park six weeks before Stanley was born. After going bankrupt, he went to Elm Park in Worcester, and drank carbolic acid. His mother removed every trace of Kunitz’s father from the household. The death of his father would be a powerful influence of his life.Kunitz and his two older sisters, Sarah and Sophia, were raised by his mother, who had made her way from Yashwen, Kovno, Lithuania by herself in 1890, and opened a dry goods store. Yetta remarried to Mark Dine in 1912. Yetta and Mark filed for bankruptcy in 1912 and then were indicted by the U.S. District Court for concealing assets. They pleaded guilty and turned over USD$10,500 to the trustees. Mark Dine died when Kunitz was fourteen, when, while hanging curtains, he suffered a heart attack.At fifteen, Kunitz moved out of the house and became a butcher’s assistant. Later he got a job as a cub reporter on The Worcester Telegram, where he would continue working during his summer vacations from college.Kunitz graduated summa cum laude in 1926 from Harvard College with an English major and a philosophy minor, and then earned a master’s degree in English from Harvard the following year. He wanted to continue his studies for a doctorate degree, but was told by the university that the Anglo-Saxon students would not like to be taught by a Jew.After Harvard, he worked as a reporter for The Worcester Telegram, and as editor for the H. W. Wilson Company in New York City. He then founded and edited Wilson Library Bulletin and started the Author Biographical Studies. Kunitz married Helen Pearce in 1930; they divorced in 1937. In 1935 he moved to New Hope, Pennsylvania and befriended Theodore Roethke. He married Eleanor Evans in 1939; they had a daughter Gretchen in 1950. Kunitz divorced Eleanor in 1958.At Wilson Company, Kunitz served as co-editor for Twentieth Century Authors, among other reference works. In 1931, as Dilly Tante, he edited Living Authors, a Book of Biographies. His poems began to appear in Poetry, Commonweal, The New Republic, The Nation, and The Dial. During World War II, he was drafted into the Army in 1943 as a conscientious objector, and after undergoing basic training three times, served as a noncombatant at Gravely Point, Washington in the Air Transport Command in charge of information and education. He refused a commission and was discharged with the rank of staff sergeant.After the war, he began a peripatetic teaching career at Bennington College (1946–1949; taking over from his friend Roethke). He subsequently taught at the State University of New York at Potsdam (then the New York State Teachers College at Potsdam) as a full professor (1949-1950; summer sessions through 1954), the New School for Social Research (lecturer; 1950-1957), the University of Washington (visiting professor; 1955-1956), Queens College (visiting professor; 1956-1957), Brandeis University (poet-in-residence; 1958-1959) and Columbia University (lecturer in the School of General Studies; 1963-1966) before spending 18 years as an adjunct professor of writing at Columbia’s School of the Arts (1967-1985). Throughout this period, he also held visiting appointments at Yale University (1970), Rutgers University–Camden (1974), Princeton University (1978) and Vassar College (1981).After his divorce from Eleanor, he married the painter and poet Elise Asher in 1958. His marriage to Asher led to friendships with artists like Philip Guston and Mark Rothko.Kunitz’s poetry won wide praise for its profundity and quality. He was the New York State Poet Laureate from 1987 to 1989. He continued to write and publish until his centenary year, as late as 2005. Many consider that his poetry’s symbolism is influenced significantly by the work of Carl Jung. Kunitz influenced many 20th-century poets, including James Wright, Mark Doty, Louise Glück, Joan Hutton Landis, and Carolyn Kizer. For most of his life, Kunitz divided his time between New York City and Provincetown, Massachusetts. He enjoyed gardening and maintained one of the most impressive seaside gardens in Provincetown. There he also founded Fine Arts Work Center, where he was a mainstay of the literary community, as he was of Poets House in Manhattan. He was awarded the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience award in Sherborn, Massachusetts in October 1998 for his contribution to the liberation of the human spirit through his poetry.He died in 2006 at his home in Manhattan. He had previously come close to death, and reflected on the experience in his last book, a collection of essays, The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden. Poetry Kunitz’s first collection of poems, Intellectual Things, was published in 1930. His second volume of poems, Passport to the War, was published fourteen years later; the book went largely unnoticed, although it featured some of Kunitz’s best-known poems, and soon fell out of print. Kunitz’s confidence was not in the best of shape when, in 1959, he had trouble finding a publisher for his third book, Selected Poems: 1928-1958. Despite this unflattering experience, the book, eventually published by Little Brown, received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. His next volume of poems would not appear until 1971, but Kunitz remained busy through the 1960s editing reference books and translating Russian poets. When twelve years later The Testing Tree appeared, Kunitz’s style was radically transformed from the highly intellectual and philosophical musings of his earlier work to more deeply personal yet disciplined narratives; moreover, his lines shifted from iambic pentameter to a freer prosody based on instinct and breath—usually resulting in shorter stressed lines of three or four beats. Throughout the 70s and 80s, he became one of the most treasured and distinctive voices in American poetry. His collection Passing Through: The Later Poems won the National Book Award for Poetry in 1995. Kunitz received many other honors, including a National Medal of Arts, the Bollingen Prize for a lifetime achievement in poetry, the Robert Frost Medal, and Harvard’s Centennial Medal. He served two terms as Consultant on Poetry for the Library of Congress (the precursor title to Poet Laureate), one term as Poet Laureate of the United States, and one term as the State Poet of New York. He founded the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and Poets House in New York City. Kunitz also acted as a judge for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition. Library Bill of Rights Kunitz served as editor of the Wilson Library Bulletin from 1928 to 1943. An outspoken critic of censorship, in his capacity as editor, he targeted his criticism at librarians who did not actively oppose it. He published an article in 1938 by Bernard Berelson entitled “The Myth of Library Impartiality”. This article led Forrest Spaulding and the Des Moines Public Library to draft the Library Bill of Rights, which was later adopted by the American Library Association and continues to serve as the cornerstone document on intellectual freedom in libraries. Awards and honors * 2006 L.L. Winship/PEN New England Award, The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden Bibliography * * Poetry * The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden (2005) * The Collected Poems of Stanley Kunitz (NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000) * Passing Through, The Later Poems, New and Selected (NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1995)—winner of the National Book Award * Next-to-Last Things: New Poems and Essays (1985) * The Wellfleet Whale and Companion Poems * The Terrible Threshold * The Coat without a Seam * The Poems of Stanley Kunitz (1928–1978) (1978) * The Testing-Tree (1971) * Selected Poems, 1928-1958 (1958) * Passport to the War (1944) * Intellectual Things (1930)Other writing and interviews: * Conversations with Stanley Kunitz (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, Literary Conversations Series, 11/2013), Edited by Kent P. Ljungquist * A Kind of Order, A Kind of Folly: Essays and Conversations’ * Interviews and Encounters with Stanley Kunitz (Riverdale-on-Hudson, NY: The Sheep Meadow Press, 1995), Edited by Stanley MossAs editor, translator, or co-translator: * The Essential Blake * Orchard Lamps by Ivan Drach * Story under full sail by Andrei Voznesensky * Poems of John Keats * Poems of Akhmatova by Max Hayward References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Kunitz

Max Ehrmann (September 26, 1872 – September 9, 1945) was an American writer, poet, and attorney from Terre Haute, Indiana, widely known for his 1927 prose poem "Desiderata" (Latin: "things desired"). He often wrote on spiritual themes. Education Ehrmann was of German descent; both his parents emigrated from Bavaria in the 1840s. Young Ehrmann was educated at the Terre Haute Fourth District School and the German Methodist Church. He received a degree in English from DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, which he attended from 1890 to 1894. While there, he was a member of Delta Tau Delta's Beta Beta chapter and was editor of the school newspaper, Depauw Weekly. Ehrmann then studied philosophy and law at Harvard University, where he was editor of Delta Tau Delta's national magazine The Rainbow, circa 1896. Professional life Ehrmann returned to his hometown of Terre Haute, Indiana in 1898 to practice law. He was a deputy state's attorney in Vigo County, Indiana for two years. Subsequently, he worked in his family's meatpacking business and in the overalls manufacturing industry (Ehrmann Manufacturing Co.) At age 40, Ehrmann left the business to write. At age 54, he wrote Desiderata, which achieved fame only after his death. Legacy Ehrmann was awarded Doctor of Letters honorary degree from DePauw University in about 1937. He was also elected to the Delta Tau Delta Distinguished Service Chapter, the fraternity's highest alumni award. Ehrmann died in 1945. He is buried in Highland Lawn Cemetery in Terre Haute, Indiana. In 2010 the city honored Ehrmann with a life-size bronze statue by sculptor Bill Wolfe. He is depicted sitting on a downtown bench, pen in hand, with a notebook in his lap. "Desiderata" is engraved on a plaque that resides next to the statue and lines from the poem are embedded in the walkway. The sculpture is in the collection of Art Spaces, Inc. – Wabash Valley Outdoor Sculpture Collection. Art Spaces also holds an annual Max Ehrmann Poetry Competition. References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Ehrmann

Aphra Behn (14 December 1640? April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, translator and fiction writer from the Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writing, she broke cultural barriers and served as a literary role model for later generations of women authors. Rising from obscurity, she came to the notice of Charles II, who employed her as a spy in Antwerp. Upon her return to London and a probable brief stay in debtors’ prison, she began writing for the stage. She belonged to a coterie of poets and famous libertines such as John Wilmot, Lord Rochester. She wrote under the pastoral pseudonym Astrea. During the turbulent political times of the Exclusion Crisis, she wrote an epilogue and prologue that brought her into legal trouble; she thereafter devoted most of her writing to prose genres and translations. A staunch supporter of the Stuart line, she declined an invitation from Bishop Burnet to write a welcoming poem to the new king William III. She died shortly after.She is remembered in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own: “All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn which is, most scandalously but rather appropriately, in Westminster Abbey, for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.” Her grave is not included in the Poets’ Corner but lies in the East Cloister near the steps to the church. Life and work Versions of her early life Information regarding Behn’s life is scant, especially regarding her early years. This may be due to intentional obscuring on Behn’s part. One version of Behn’s life tells that she was born to a barber named John Amis and his wife Amy. Another story has Behn born to a couple named Cooper. The Histories And Novels of the Late Ingenious Mrs. Behn (1696) states that Behn was born to Bartholomew Johnson, a barber, and Elizabeth Denham, a wet-nurse. Colonel Thomas Colepeper, the only person who claimed to have known her as a child, wrote in Adversaria that she was born at “Sturry or Canterbury” to a Mr Johnson and that she had a sister named Frances. Another contemporary, Anne Finch, wrote that Behn was born in Wye in Kent, the “Daughter to a Barber”. In some accounts the profile of her father fits Eaffrey Johnson.Behn was born during the buildup of the English Civil War, a child of the political tensions of the time. One version of Behn’s story has her travelling with a Bartholomew Johnson to Surinam. He was said to die on the journey, with his wife and children spending some months in the country, though there is no evidence of this. During this trip Behn said she met an African slave leader, whose story formed the basis for one of her most famous works, Oroonoko. It is possible that she acted a spy in the colony. There is little verifiable evidence to confirm any one story. In Oroonoko Behn gives herself the position of narrator and her first biographer accepted the assumption that Behn was the daughter of the lieutenant general of Surinam, as in the story. There is little evidence that this was the case, and none of her contemporaries acknowledge any aristocratic status. There is also no evidence that Oroonoko existed as an actual person or that any such slave revolt, as is featured in the story, really happened. Writer Germaine Greer has called Behn “a palimpsest; she has scratched herself out,” and biographer Janet Todd noted that Behn “has a lethal combination of obscurity, secrecy and staginess which makes her an uneasy fit for any narrative, speculative or factual. She is not so much a woman to be unmasked as an unending combination of masks”. It is notable that her name is not mentioned in tax or church records. During her lifetime she was also known as Ann Behn, Mrs Bean, agent 160 and Astrea. Career Shortly after her supposed return to England from Surinam in 1664, Behn may have married Johan Behn (also written as Johann and John Behn). He may have been a merchant of German or Dutch extraction, possibly from Hamburg. He died or the couple separated soon after 1664, however from this point the writer used “Mrs Behn” as her professional name.Behn may have had a Catholic upbringing. She once commented that she was “designed for a nun,” and the fact that she had so many Catholic connections, such as Henry Neville who was later arrested for his Catholicism, would have aroused suspicions during the anti-Catholic fervour of the 1680s. She was a monarchist, and her sympathy for the Stuarts, and particularly for the Catholic Duke of York may be demonstrated by her dedication of her play The Rover II to him after he had been exiled for the second time. Behn was dedicated to the restored King Charles II. As political parties emerged during this time, Behn became a Tory supporter.By 1666 Behn had become attached to the court, possibly through the influence of Thomas Culpeper and other associates. The Second Anglo-Dutch War had broken out between England and the Netherlands in 1665, and she was recruited as a political spy in Antwerp on behalf of King Charles II, possibly under the auspices of courtier Thomas Killigrew. This is the first well-documented account we have of her activities. Her code name is said to have been Astrea, a name under which she later published many of her writings. Her chief role was to establish an intimacy with William Scot, son of Thomas Scot, a regicide who had been executed in 1660. Scot was believed to be ready to become a spy in the English service and to report on the doings of the English exiles who were plotting against the King. Behn arrived in Bruges in July 1666, probably with two others, as London was wracked with plague and fire. Behn’s job was to turn Scot into a double agent, but there is evidence that Scot betrayed her to the Dutch.Behn’s exploits were not profitable however; the cost of living shocked her, and she was left unprepared. One month after arrival, she pawned her jewellry. King Charles was slow in paying (if he paid at all), either for her services or for her expenses whilst abroad. Money had to be borrowed so that Behn could return to London, where a year’s petitioning of Charles for payment was unsuccessful. It may be that she was never paid by the crown. A warrant was issued for her arrest, but there is no evidence it was served or that she went to prison for her debt, though apocryphally it is often given as part of her history. Forced by debt and her husband’s death, Behn began to work for the King’s Company and the Duke’s Company players as a scribe. She had, however, written poetry up until this point. While she is recorded to have written before she adopted her debt, John Palmer said in a review of her works that, “Mrs. Behn wrote for a livelihood. Playwriting was her refuge from starvation and a debtor’s prison.” The theatres that had been closed under Cromwell were now re-opening under Charles II, plays enjoying a revival. Her first play, The Forc’d Marriage, was staged in 1670, followed by The Amorous Prince (1671). After her third play, The Dutch Lover, failed, Behn falls off the public record for three years. It is speculated that she went travelling again, possibly in her capacity as a spy. She gradually moved towards comic works, which proved more commercially successful. Her most popular works included The Rover. Behn became friends with notable writers of the day, including John Dryden, Elizabeth Barry, John Hoyle, Thomas Otway and Edward Ravenscroft, and was acknowledged as a part of the circle of the Earl of Rochester. Behn often used her writings to attack the parliamentary Whigs claiming, “In public spirits call’d, good o’ th’ Commonwealth... So tho’ by different ways the fever seize... in all ’tis one and the same mad disease.” This was Behn’s reproach to parliament which had denied the king funds. Final years and death In 1688, in the year before her death, she published A Discovery of New Worlds, a translation of a French popularisation of astronomy, Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes, by Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, written as a novel in a form similar to her own work, but with her new, religiously oriented preface. In all she would write and stage 19 plays, contribute to more, and become one of the first prolific, high-profile female dramatists in Britain. During the 1670s and 1680s she was one of the most productive playwrights in Britain, second only to Poet Laureate John Dryden.In her last four years, Behn’s health began to fail, beset by poverty and debt, but she continued to write ferociously, though it became increasingly hard for her to hold a pen. In her final days, she wrote the translation of the final book of Abraham Cowley’s Six Books of Plants. She died on 16 April 1689, and was buried in the East Cloister Westminster Abbey. The inscription on her tombstone reads: “Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.” She was quoted as stating that she had led a “life dedicated to pleasure and poetry.” Published works Behn earned a living writing, one of the earliest Englishwoman to do so. After John Dryden she was the most prolific writer of the English Restoration. Behn was not the first woman in England to publish a play. In 1613 Lady Elizabeth Cary had published The Tragedy of Miriam, in the 1650s Margaret Cavendish published two volumes of plays, and in 1663 a translation of Corneille’s Pompey by Katherine Philips was performed in Dublin and London. Women had been excluded from theatre in the Elizabethan era, but in Restoration England they made up a significant part of the audience and professional actresses played the women’s parts. This changed the nature and themes of Restoration theatre.Behn’s first play The Forc’d Marriage was a romantic tragicomedy on arranged marriages and was staged by the Duke’s Company in September 1670. The performance ran for six nights, which was regarded as a good run for an unknown author. Six months later Behn’s play The Amorous Prince was successfully staged. Again, Behn used the play to comment on the harmful effects of arranged marriages. Behn did not hide the fact that she was a woman, instead she made a point of it. When in 1673 the Dorset Garden Theatre staged The Dutch Lover, critics sabotaged the play on the grounds that the author was a woman. Behn tackled the critics head on in Epistle to the Reader. She argued that women had been held back by their unjust exclusion from education, not their lack of ability. After a three-year publication pause, Behn published four plays in close succession. In 1676 she published Abdelazar, The Town Fop and The Rover. In early 1678 Sir Patient Fancy was published. This succession of box-office successes led to frequent attacks on Behn. She was attacked for her private life, the morality of her plays was questioned and she was accused of plagiarising The Rover. Behn countered these public attacks in the prefaces of her published plays. In the preface to Sir Patient Fancy she argued that she was being singled out because she was a woman, while male playwrights were free to live the most scandalous lives and write bawdy plays.Under Charles II of England prevailing Puritan ethics was reversed in the fashionable society of London. The King associated with playwrights that poured scorn on marriage and the idea of consistency in love. Among the King’s favourite was the Earl of Rochester John Wilmot, who became famous for his cynical libertinism. Behn was a friend of Wilmot and Behn became a bold proponent of sexual freedom for both women and men. Like her contemporary male libertines, she wrote freely about sex. In the infamous poem The Disappointment she wrote a comic account of male impotence from a woman’s perspective. Critics Lisa Zeitz and Peter Thoms contend that the poem “playfully and wittily questions conventional gender roles and the structures of oppression which they support”. In The Dutch Lover Behn forthrightly acknowledged female sexual desire. Critics of Behn were provided with ammunition because of her public liaison with John Hoyle, a bisexual lawyer who scandalised his contemporaries.By the late 1670s Behn was among the leading playwrights of England. Her plays were staged frequently and attended by the King. The Rover became a favourite at the King’s court. Behn became heavily involved in the political debate about the succession. Because Charles II had no heir a prolonged political crisis ensued. Mass hysteria commenced as in 1678 the rumoured Popish Plot suggested the King should be replaced with his Roman Catholic brother James. Political parties developed, the Whigs wanted to exclude James, while the Tories did not believe succession should be altered in any way. Charles II eventually dissolved the Cavalier Parliament and James II succeeded him in 1685. Behn supported the Tory position and in the two years between 1681 and 1682 produced five plays to discredit the Whigs. The London audience, mainly Tory sympathisers, attended the plays in large numbers. But Behn was arrested on the order of King Charles II when she used one of the plays to attack James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, the illegitimate son of the King.As audience numbers declined, theatres staged mainly old works to save costs. Nevertheless, Behn published The Luckey Chance in 1686. In response to the criticism levelled at they play she articulated a long and passionate defence of women writers. Her play The Emperor of the Moon was published and staged in 1687, it became one of her longest running plays. Behn stopped writing plays and turned to prose fiction. Today she is mostly known for the novels she wrote in the later part of her life. Her first novel was the three-part Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister, published between 1682 and 1687. The novels were inspired by a contemporary scandal, which saw Lord Grey elope with his sister-in-law Lady Henrietta Berkeley. At the time of publication Love Letters was very popular and went through more than 16 editions. Today Behn’s prose work is critically acknowledged as having been important to the development of the English novel. Following Behn’s death, new female dramatists such as Delarivier Manley, Mary Pix, Susanna Centlivre and Catherine Trotter acknowledged Behn as their most vital predecessor, who opened up public space for women writers.In 1688, less than a year before her death, Behn published Oroonoko: or, The Royal Oroonoko, the story of the enslaved Oroonoko and his love Imoinda. It was based on Behn’s travel to Surinam twenty years earlier. The novel became a great success. In 1696 it was adapted for the stage by Thomas Southerne and continuously performed throughout the 18th century. In 1745 the novel was translated into French, going through seven French editions. As abolitionism gathered pace in the late 18th century the novel was celebrated as the first anti-slavery novel. Legacy and re-evaluation After her death in 1689 Behn’s literary work was marginalised and dismissed outright. Until the mid-20th century Behn was repeatedly dismissed as morally depraved minor writer. In the 18th century her literary work was scandalised as lewd by Thomas Brown, William Wycherley, Richard Steele and John Duncombe. Alexander Pope penned the famous lines “The stage how loosely does Astrea tread, Who fairly puts all characters to bed!”. In the 19th century Mary Hays, Matilda Betham, Alexander Dyce, Jane Williams and Julia Kavanagh decided that Behn’s writings were unfit to read, because they were corrupt and deplorable. Among the few critics who believed that Behn was an important writer were Leigh Hunt, William Forsyth and William Henry Hudson.The life and times of Behn were recounted by a long line of biographers, among them Dyce, Edmund Gosse, Ernest Bernbaum, Montague Summers, Vita Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf, George Woodcock, William J. Cameron and Frederick Link.Of Behn’s considerable literary output only Oroonoko was seriously considered by literary scholars. The late 18th century the novel is regarded as one of the first abolitionist and humanitarian novel published in the English language. It is credited as precursor to Jean-Jaques Rousseau’s Discourses on Inequality. Since the 1970s Behn’s literary works have been re-evaluated by feminist critics and writers. Behn was rediscovered as a significant female writer by Maureen Duffy, Angeline Goreau, Ruth Perry, Hilda Lee Smith, Moira Ferguson, Jane Spencer, Dale Spender, Elaine Hobby and Janet Todd. This led to the reprinting of her works. The Rover was republished in 1967, Oroonoko was republished in 1973, Love Letters between a Nobleman and His Sisters was published again in 1987 and The Lucky Chance was reprinted in 1988. Montague Summers, an author of scholarly works on the English drama of the 17th century, published a six-volume collection of her work, in hopes of rehabilitating her reputation. Summers was fiercely passionate about the work of Behn and found himself incredibly devoted to the appreciation of 17th century literature. Felix Schelling wrote in The Cambridge History of English Literature, that she was “a very gifted woman, compelled to write for bread in an age in which literature... catered habitually to the lowest and most depraved of human inclinations,” and that, “Her success depended upon her ability to write like a man.” Edmund Gosse remarked that she was, “...the George Sand of the Restoration”.The criticism of Behn’s poetry focuses on the themes of gender, sexuality, femininity, pleasure, and love. A feminist critique tends to focus on Behn’s inclusion of female pleasure and sexuality in her poetry, which was a radical concept at the time she was writing. One critic, Alison Conway, views Behn as instrumental to the formation of modern thought around the female gender and sexuality: "Behn wrote about these subjects before the technologies of sexuality we now associate were in place, which is, in part, why she proves so hard to situate in the trajectories most familiar to us”. Virginia Woolf wrote, in A Room of One’s Own: All women together, ought to let flowers fall upon the grave of Aphra Behn... for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds... Behn proved that money could be made by writing at the sacrifice, perhaps, of certain agreeable qualities; and so by degrees writing became not merely a sign of folly and a distracted mind but was of practical importance. Adaptations of Behn in Literature Behn’s life has been adapted for the stage in the 2014 play Empress of the Moon: The Lives of Aphra Behn by Chris Braak, and the 2015 play [exit Mrs Behn] or, The Leo Play by Christopher VanderArk. She is one of the characters in the 2010 play Or, by Liz Duffy Adams. Behn appears as a character in Daniel O’Mahony’s Newtons Sleep, in Phillip Jose Farmer’s The Magic Labyrinth and Gods of Riverworld, in Molly Brown’s Invitation to a Funeral (1999), and in Diana Norman’s The Vizard Mask. She is referred to in Patrick O’Brian’s novel Desolation Island.

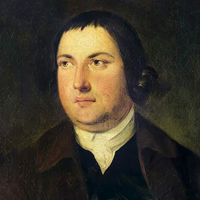

George Chapman (Hitchin, Hertfordshire, C. 1559– London,12 May 1634) was an English dramatist, translator, and poet. He was a classical scholar whose work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman has been identified as the Rival Poet of Shakespeare’s sonnets by William Minto, and as an anticipator of the Metaphysical Poets of the 17th century. Chapman is best remembered for his translations of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and the Homeric Batrachomyomachia. Life and work Chapman was born at Hitchin in Hertfordshire. There is conjecture that he studied at Oxford but did not take a degree, though no reliable evidence affirms this. Very little is known about Chapman’s early life, but Mark Eccles uncovered records that reveal much about Chapman’s difficulties and expectations. In 1585 Chapman was approached in a friendly fashion by John Wolfall, Sr., who offered to supply a bond of surety for a loan to furnish Chapman money “for his proper use in Attendance upon the then Right Honorable Sir Rafe Sadler Knight.” Chapman’s courtly ambitions led him into a trap. He apparently never received any money, but he would be plagued for many years by the papers he had signed. Wolfall had the poet arrested for debt in 1600, and when in 1608 Wolfall’s son, having inherited his father’s papers, sued yet again, Chapman’s only resort was to petition the Court of Chancery for equity. As Sadler died in 1587, this gives Chapman little time to have trained under him. It seems more likely that he was in Sadler’s household from 1577–83, as he dedicates all his Homerical translations to him. Chapman spent the early 1590s abroad, and saw military action in the Low Countries fighting under renowned English general Sir Francis Vere. His earliest published works were the obscure philosophical poems The Shadow of Night (1594) and Ovid’s Banquet of Sense (1595). The latter has been taken as a response to the erotic poems of the age, such as Philip Sidney’s Astrophil and Stella and Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis. Chapman’s life was troubled by debt and his inability to find a patron whose fortunes did not decline: Robert Devereux, Second Earl of Essex and the Prince of Wales, Prince Henry both met their ends prematurely. The former was executed for treason by Elizabeth I in 1601, and the latter died of typhoid fever at the age of eighteen in 1612. Chapman’s resultant poverty did not diminish his ability or his standing among his fellow Elizabethan poets and dramatists. Chapman died in London, having lived his latter years in poverty and debt. He was buried at St Giles in the Fields. A monument to him designed by Inigo Jones marked his tomb, and stands today inside the church. Plays Comedies By the end of the 1590s, Chapman had become a successful playwright, working for Philip Henslowe and later for the Children of the Chapel. Among his comedies are The Blind Beggar of Alexandria (1596; printed 1598), An Humorous Day’s Mirth (1597; printed 1599), All Fools (printed 1605), Monsieur D’Olive (1605; printed 1606), The Gentleman Usher (printed 1606), May Day (printed 1611), and The Widow’s Tears (printed 1612). His plays show a willingness to experiment with dramatic form: An Humorous Day’s Mirth was one of the first plays to be written in the style of “humours comedy” which Ben Jonson later used in Every Man in his Humour and Every Man Out of his Humour. With The Widow’s Tears, he was also one of the first writers to meld comedy with more serious themes, creating the tragicomedy later made famous by Beaumont and Fletcher. He also wrote one noteworthy play in collaboration. Eastward Ho (1605), written with Jonson and John Marston, contained satirical references to the Scots which landed Chapman and Jonson in jail. Various of their letters to the king and noblemen survive in a manuscript in the Folger Library known as the Dobell MS, and published by AR Braunmuller as A Seventeenth Century Letterbook. In the letters, both men renounced the offending line, implying that Marston was responsible for the injurious remark. Jonson’s “Conversations With Drummond” refers to the imprisonment, and suggests there was a possibility that both authors would have their “ears and noses slit” as a punishment, but this may have been Jonson elaborating on the story in retrospect. Chapman’s friendship with Jonson broke down, perhaps as a result of Jonson’s public feud with Inigo Jones. Some satiric, scathing lines, written sometime after the burning of Jonson’s desk and papers, provide evidence of the rift. The poem lampooning Jonson’s aggressive behaviour and self-believed superiority remained unpublished during Chapman’s lifetime; it was found in documents collected after his death. Tragedies Chapman’s greatest tragedies took their subject matter from recent French history, the French ambassador taking offence on at least one occasion. These include Bussy D’Ambois (1607), The Conspiracy and Tragedy of Charles, Duke of Byron (1608), The Revenge of Bussy D’Ambois (1613) and The Tragedy of Chabot, Admiral of France (published 1639). The two Byron plays were banned from the stage—although, when the Court left London, the plays were performed in their original and unexpurgated forms by the Children of the Chapel. The French ambassador probably took offence to a scene which portrays Henry IV’s wife and mistress arguing and physically fighting. On publication, the offending material was excised, and Chapman refers to the play in his dedication to Sir Thomas Walsingham as “poore dismembered Poems.” His only work of classical tragedy, Caesar and Pompey (ca. 1613?) is generally regarded as his most modest achievement in the genre. Other plays Chapman wrote one of the most successful masques of the Jacobean era, The Memorable Masque of the Middle Temple and Lincoln’s Inn, performed on 15 February 1613. According to Kenneth Muir, The Masque of the Twelve Months, performed on Twelfth Night 1619 and first printed by John Payne Collier in 1848 with no author’s name attached, is also ascribed to Chapman. Chapman’s authorship has been argued in connection with a number of other anonymous plays of his era. F. G. Fleay proposed that his first play was The Disguises. He has been put forward as the author, in whole or in part, of Sir Giles Goosecap, Two Wise Men And All The Rest Fools, The Fountain Of New Fashions, and The Second Maiden’s Tragedy. Of these, only 'Sir Gyles Goosecap’ is generally accepted by scholars to have been written by Chapman (The Plays of George Chapman: The Tragedies, with Sir Giles Goosecap, edited by Allan Holaday, University of Illinois Press, 1987). In 1654, bookseller Richard Marriot published the play Revenge for Honour as the work of Chapman. Scholars have rejected the attribution; the play may have been written by Henry Glapthorne. Alphonsus Emperor of Germany (also printed 1654) is generally considered another false Chapman attribution. The lost plays The Fatal Love and A Yorkshire Gentlewoman And Her Son were assigned to Chapman in Stationers’ Register entries in 1660. Both of these plays were among the ones destroyed in the famous kitchen burnings by John Warburton’s cook. The lost play Christianetta (registered 1640) may have been a collaboration between Chapman and Richard Brome, or a revision by Brome of a Chapman work. Poet and translator Other poems by Chapman include: De Guiana, Carmen Epicum (1596), on the exploits of Sir Walter Raleigh; a continuation of Christopher Marlowe’s unfinished Hero and Leander (1598); and Euthymiae Raptus; or the Tears of Peace (1609). Some have considered Chapman to be the “rival poet” of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. From 1598 he published his translation of the Iliad in installments. In 1616 the complete Iliad and Odyssey appeared in The Whole Works of Homer, the first complete English translation, which until Pope’s was the most popular in the English language and was the way most English speakers encountered these poems. The endeavour was to have been profitable: his patron, Prince Henry, had promised him £300 on its completion plus a pension. However, Henry died in 1612 and his household neglected the commitment, leaving Chapman without either a patron or an income. In an extant letter, Chapman petitions for the money owed him; his petition was ineffective. Chapman’s translation of the Odyssey is written in iambic pentameter, whereas his Iliad is written in iambic heptameter. (The Greek original is in dactylic hexameter.) Chapman often extends and elaborates on Homer’s original contents to add descriptive detail or moral and philosophical interpretation and emphasis. Chapman’s translation of Homer was much admired by John Keats, notably in his famous poem On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer, and also drew attention from Samuel Taylor Coleridge and T. S. Eliot. Chapman also translated the Homeric Hymns, the Georgics of Virgil, The Works of Hesiod (1618, dedicated to Francis Bacon), the Hero and Leander of Musaeus (1618), and the Fifth Satire of Juvenal (1624). Chapman’s poetry, though not widely influential on the subsequent development of English poetry, did have a noteworthy effect on the work of T. S. Eliot. Homage In Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem The Revolt of Islam, Shelley quotes a verse of Chapman’s as homage within his dedication "to Mary__ __", presumably his wife Mary Shelley: There is no danger to a man, that knows What life and death is: there's not any law Exceeds his knowledge; neither is it lawful That he should stoop to any other law. The Irish playwright Oscar Wilde quoted the same verse in his part fiction, part literary criticism, “The Portrait of Mr. W.H.”. The English poet John Keats wrote “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” for his friend Charles Cowden Clarke in October 1816. The poem begins “Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold” and is much quoted. For example, P. G. Wodehouse in his review of the first novel of The Flashman Papers series that came to his attention: “Now I understand what that 'when a new planet swims into his ken’ excitement is all about.” Arthur Ransome uses two references from it in his children’s books, the Swallows and Amazons series. Quotes From All Fooles, II.1.170-178, by George Chapman: I could have written as good prose and verse As the most beggarly poet of 'em all, Either Accrostique, Exordion, Epithalamions, Satyres, Epigrams, Sonnets in Doozens, or your Quatorzanies, In any rhyme, Masculine, Feminine, Or Sdrucciola, or cooplets, Blancke Verse: Y'are but bench-whistlers now a dayes to them That were in our times.... References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Chapman

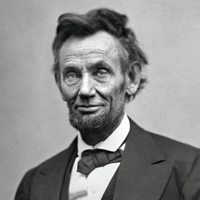

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809– April 15, 1865) was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. Lincoln led the United States through its Civil War—its bloodiest war and an event often considered its greatest moral, constitutional, and political crisis. In doing so, he preserved the Union, abolished slavery, strengthened the federal government, and modernized the economy. Born in Hodgenville, Kentucky, Lincoln grew up on the western frontier in Kentucky and Indiana. Largely self-educated, he became a lawyer in Illinois, a Whig Party leader, and a member of the Illinois House of Representatives, in which he served for twelve years.

Robert Bly (born December 23, 1926) is an American poet, author, activist and leader of the mythopoetic men’s movement. His most commercially successful book to date was Iron John: A Book About Men (1990), a key text of the mythopoetic men’s movement, which spent 62 weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list. He won the 1968 National Book Award for Poetry for his book The Light Around the Body. Life Bly was born in Lac qui Parle County, Minnesota, to Jacob and Alice Bly, who were of Norwegian ancestry. Following graduation from high school in 1944, he enlisted in the United States Navy, serving two years. After one year at St. Olaf College in Minnesota, he transferred to Harvard University, joining the later famous group of writers who were undergraduates at that time, including Donald Hall, Will Morgan, Adrienne Rich, Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Harold Brodkey, George Plimpton and John Hawkes. He graduated in 1950 and spent the next few years in New York. Beginning in 1954, Bly spent two years at the University of Iowa at the Iowa Writers Workshop, completing a master’s degree in fine arts, along with W. D. Snodgrass, Donald Justice, and others. In 1956, he received a Fulbright Grant to travel to Norway and translate Norwegian poetry into English. While there, he found not only his relatives, but became acquainted with the work of a number of major poets whose work was barely known in the United States, among them Pablo Neruda, Cesar Vallejo, Antonio Machado, Gunnar Ekelof, Georg Trakl, Rumi, Hafez, Kabir, Mirabai, and Harry Martinson. Bly determined then to start a literary magazine for poetry translation in the United States. The Fifties, The Sixties, and The Seventies introduced many of these poets to the writers of his generation. He also published essays on American poets. During this time, Bly lived on a farm in Minnesota, with his wife and children. His first marriage was to award-winning short story novelist Carol Bly. They had four children, including Mary Bly—a best-selling novelist and Literature Professor at Fordham University as of 2011—and they divorced in 1979. Since 1980 Bly has been married to the former Ruth Counsell; by that marriage he had a stepdaughter and stepson, although the stepson died in a pedestrian–train incident. Career Bly’s early collection of poems, Silence in the Snowy Fields, was published in 1962, and its plain, imagistic style had considerable influence on American verse of the next two decades. The following year, he published “A Wrong Turning in American Poetry”, an essay in which he argued that the vast majority of American poetry from 1917 to 1963 was lacking in soul and “inwardness” as a result of a focus on impersonality and an objectifying, intellectual view of the world that Bly believed was instigated by the Modernists and formed the aesthetic of most post-World War II American poetry. He criticized the influence of American-born Modernists like Eliot, Pound, Marianne Moore, and William Carlos Williams and argued that American poetry needed to model itself on the more inward-looking work of European and South American poets like Pablo Neruda, César Vallejo, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Antonio Machado, and Rainer Maria Rilke. In 1966, Bly co-founded American Writers Against the Vietnam War and went on to lead much of the opposition to that war among writers. In 1968, he signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the war. In his speech accepting the National Book Award for The Light Around the Body, he announced that he would be contributing the $1000 prize to draft resistance organizations. During the sixties he was of great help to the Bengali Hungryalist poets who faced anti-establishment trial at Kolkata, India. Bly became one of the most important of American protest poets during the Vietnam War; his 1970 poem “The Teeth Mother Naked At Last,” later collected in his collection Sleepers Joining Hands (1973) is a major contribution to this poetry. During the 1970s, he published eleven books of poetry, essays, and translations, celebrating the power of myth, Indian ecstatic poetry, meditation, and storytelling. During the 1980s he published Loving a Woman in Two Worlds, The Wingéd Life: Selected Poems and Prose of Thoreau, The Man in the Black Coat Turns, and A Little Book on the Human Shadow. In 1975, he organized the first annual Great Mother Conference. Throughout the ten-day event, poetry, music, and dance were utilized to examine human consciousness. The conference has been held annually through 2015 in Nobleboro Maine. In the beginning one of its major themes was the goddess or “Great Mother” as she has been known throughout human history. Much of Bly’s 1973 book of poems “Sleepers Joining Hands” is concerned with this theme. In the context of the Vietnam War, a focus on the divine feminine was seen as urgent and necessary. Since that time, the Conference has expanded to consider a wide variety of poetic, mythological, and fairy tale traditions. In the ’80s and ’90s there was much discussion among the conference community about the changes contemporary men were (and are) going through; “the New Father” was then added to the Conference title, in recognition of this and in order to keep the Conference as inclusive as possible. Perhaps his most famous work is Iron John: A Book About Men (1990), an international bestseller which has been translated into many languages and is credited with starting the Mythopoetic men’s movement in the United States. Bly frequently conducts workshops for men with James Hillman, Michael J. Meade, and others, as well as workshops for men and women with Marion Woodman. He maintains a friendly correspondence with Clarissa Pinkola Estés, author of Women Who Run With the Wolves. Bly wrote The Maiden King: The Reunion of Masculine and Feminine with Marion Woodman. Bly was the University of Minnesota Library’s 2002 Distinguished Writer. He received the McKnight Foundation’s Distinguished Artist Award in 2000, and the Maurice English Poetry Award in 2002. He has published more than 40 collections of poetry, edited many others, and published translations of poetry and prose from such languages as Swedish, Norwegian, German, Spanish, Persian and Urdu. His book The Night Abraham Called to the Stars was nominated for a Minnesota Book Award. He also edited the prestigious Best American Poetry 1999 (Scribners). In 2006 the University of Minnesota purchased Bly’s archive, which contained more than 80,000 pages of handwritten manuscripts; a journal spanning nearly 50 years; notebooks of his “morning poems”; drafts of translations; hundreds of audio and videotapes, and correspondence with many writers such as James Wright, Donald Hall and James Dickey. The archive is housed at Elmer L. Andersen Library on the University of Minnesota campus. The university paid $775,000 from school funds and private donors. In February 2008, Bly was named Minnesota’s first poet laureate. In that year he also contributed a poem and an Afterword to From the Other World: Poems in Memory of James Wright. In February 2013, he was awarded the Robert Frost Medal, a lifetime achievement recognition given by the Poetry Society of America. Thought and the Men’s Movement Much of Bly’s writing focuses on what he saw as the particularly troubled situation in which many males find themselves today. He understood this to be a result of, among other things, the decline of traditional fathering which left young boys unguided through the stages of life leading to maturity. He claimed that in contrast with women who are better informed by their bodies (notably by the beginning and end of their menstrual cycle), men need to be actively guided out of boyhood and into manhood by their elders. Pre-modern cultures had elaborate myths, often enacted as rites of passage, as well as “men’s societies” where older men would teach young boys about these gender-specific issues. As modern fathers have become increasingly absent, this knowledge is no longer being passed down the generations, resulting in what he referred to as a Sibling Society. The “Absence of the Father” is a recurrent theme in Bly’s work and many of the phenomena of depression, juvenile delinquency and lack of leadership in business and politics are linked to it. Bly therefore sees today’s men as half-adults, trapped between boyhood and maturity, in a state where they find it hard to become responsible in their work as well as leaders in their communities. Eventually they might become weak or absent fathers themselves which will lead this behaviour to be passed down to their children. In his book The Sibling Society (1997), Bly argues that a society formed of such men is inherently problematic as it lacks creativity and a deep sense of empathy. The image of half-adults is further reinforced by popular culture which often portrays fathers as naive, overweight and almost always emotionally co-dependent. Historically this represents a recent shift from a traditional patriarchal model and Bly believes that women rushed to fill the gap that was formed through the various youth movements during the 1960s, enhancing men’s emotional capacities and helping them to connect with women’s age-old pain of repression. It has however also led to the creation of “soft males” which lacked the outwardly directed strength to revitalize the community with assertiveness and a certain warrior strength. In Bly’s view, a potential solution lies in the rediscovery of the meanings hidden in traditional myths and fairytales as well as works of poetry. He researched and collected myths that concern male maturity, often originating from the Grimms’ Fairy Tales and published them in various books, Iron John being the best known example. In contrast to the continual pursuit of higher achievements, that is constantly taught to young men today, the theme of spiritual descent (often being referred to by its Greek term κατάβασις) which is to be found in many of these myths, is presented as a necessary step for coming in contact with the deeper aspects of the masculine self and achieving its full potential. This is often presented as hero, often during the middle of his quest, going underground to pass a period of solitude and sorrow in semi-bestial mode. Bly notices that a cultural space existed in most traditional societies for such a period in a man’s life, in the absence of which, many men today go into a depression and alcoholism as they subconsciously try to emulate this innate ritual. Bly was influenced by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung who developed the theory of archetypes, as the discrete structures of the Psyche which emerge as images in both art and myths. The Powerful King, the Evil Witch and the Beautiful Maiden are, according to Jung, imprints of the collective unconscious and Bly wrote extensively about their meaning and relations to modern life. As an example and in accordance with Jung, he considered the Witch to be that part of the male psyche upon which the negative and destructive side of a woman is imprinted and which first developed during infancy to store the imperfections of one’s own mother’s. As a consequence, the Witch’s symbols are essentially inverted motherly symbols, where the loving act of cooking is transformed into the brewing of evil potions and knitting clothes takes the form of spider’s web. The feeding process is also reversed, with the child now in danger of being eaten to feed the body of the Witch rather than being fed by the mother’s own body. In that respect, the Witch is a mark of arrested development on the part of the man as it guards against feminine realities that the his psyche is not yet able to incorporate fully. Fairy tales according to this interpretation mostly describe internal battles laid out in externally, where the hero saves his future bride by killing a witch, as in “The Drummer” (Grimms tale 193). This particular concept is expanded in Bly’s 1989 talk “The Human Shadow” and the book it presented. Works References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Bly

Nicholas Breton (also Britton or Brittaine) (1545–1626), English poet and novelist, belonged to an old family settled at Layer Breton, Essex. Life His father, William Breton, a London merchant who had made a considerable fortune, died in 1559, and the widow (née Elizabeth Bacon) married the poet George Gascoigne before her sons had attained their majority. Nicholas Breton was probably born at the “capitall mansion house” in Red Cross Street, in the parish of St Giles without Cripplegate, mentioned in his father’s will. There is no official record of his residence at the university, but the diary of the Rev. Richard Madox tells us that he was at Antwerp in 1583 and was “once of Oriel College.” He married Ann Sutton in 1593, and had a family. He is supposed to have died shortly after the publication of his last work, Fantastickes (1626). Breton found a patron in Mary, countess of Pembroke, and wrote much in her honour until 1601, when she seems to have withdrawn her favour. It is probably safe to supplement the meagre record of his life by accepting as autobiographical some of the letters signed N.B. in A Poste with a Packet of Mad Letters (1603, enlarged 1637); the 19th letter of the second part contains a general complaint of many griefs, and proceeds as follows: “Hath another been wounded in the warres, fared hard, lain in a cold bed many a bitter storme, and beene at many a hard banquet? all these have I; another imprisoned? so have I; another long been sicke? so have I; another plagued with an unquiet life? so have I; another indebted to his hearts griefe, and fame would pay and cannot? so am I.” Works * Breton was a prolific author of considerable versatility and gift, popular with his contemporaries, and forgotten by the next generation. His work consists of religious and pastoral poems, satires, and a number of miscellaneous prose tracts. His religious poems are sometimes wearisome by their excess of fluency and sweetness, but they are evidently the expression of a devout and earnest mind. His lyrics are pure and fresh, and his romances, though full of conceits, are pleasant reading, remarkably free from grossness. His praise of the Virgin and his references to Mary Magdalene have suggested that he was a Roman Catholic, but his prose writings abundantly prove that he was an ardent Anglican. * Breton had little gift for satire, and his best work is to be found in his pastoral poetry. His Passionate Shepheard (1604) is full of sunshine and fresh air, and of unaffected gaiety. The third pastoral in this book—"Who can live in heart so glad As the merrie country lad"—is well known; with some other of Breton’s daintiest poems, among them the lullaby, “Come little babe, come silly soule,” (This poem, however, comes from The Arbor of Amorous Devises, which is only in part Breton’s work.)—it is incorporated in A. H. Bullen’s Lyrics from Elizabethan Romances (1890). His keen observation of country life appears also in his prose idyll, Wits Trenckrnour, “a conference betwixt a scholler and an angler,” and in his Fantastickes, a series of short prose pictures of the months, the Christian festivals and the hours, which throw much light on the customs of the times. Most of Breton’s books are very rare and have great bibliographical value. His works, with the exception of some belonging to private owners, were collected by Dr AB Grosart in the Chertsey Worthies Library in 1879, with an elaborate introduction quoting the documents for the poet’s history. * Breton’s poetical works, the titles of which are here somewhat abbreviated, include: * The Workes of a Young Wit (1577) * A Floorish upon Fancie (1577) * The Pilgrimage to Paradise (1592), with a prefatory letter by John Case * The Countess of Penbrook’s Passion (manuscript), first printed by JO Halliwell-Phillipps in 1853 [1] * Pasquil’s Fooles cappe (entered at Stationers’ Hall in 1600) * Pasquil’s Mistresse (1600) * Pasquil’s Passe and Passeth Not (1600) * Melancholike Humours (1600) - reprinted by Scholartis Press London. 1929. * Marie Magdalen’s Love: a Solemne Passion of the Soules Love (1595), the first part of which, a prose treatise, is probably by another hand; the second part, a poem in six-lined stanza, is certainly by Breton * A Divine Poem, including “The Ravisht Soul” and “The Blessed Weeper” (1601) * An Excellent Poem, upon the Longing of a Blessed heart (1601) * The Soules Heavenly Exercise (1601) * The Soules Harmony (1602) * Olde Madcappe newe Gaily mawfrey (1602) * The Mother’s Blessing (1602) * A True Description of Unthankfulnesse (1602) * The Passionate Shepheard (1604) * The Souies Immortail Crowne (1605) * The Honour of Valour (1605) * An Invective against Treason; I would and I would not (1614) * Bryton’s Bowre of Delights (1591), edited by Dr Grosart in 1893, an unauthorized publication which contained some poems disclaimed by Breton * The Arbor of Amorous Devises (entered at Stationers’ Hall, 1594), only in part Breton’s * contributions to England’s Helicon and other miscellanies of verse. * Of his twenty-two prose tracts may be mentioned Wit’s Trenchmour (1597), The Wil of Wit (1599), A Poste with a Packet of Mad Letters (1602-6). Sir Philip Sidney’s Ourania by N. B. (1606), A Mad World, my Masters, Adventures of Two Excellent Princes, Grimello’s Fortunes (1603), Strange News out of Divers Countries (1622), etc.; Mary Magdalen’s Lamentations (1604), and The Passion of a Discontented Mind (1601), are sometimes, but erroneously, ascribed to Breton. Footnotes References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Breton