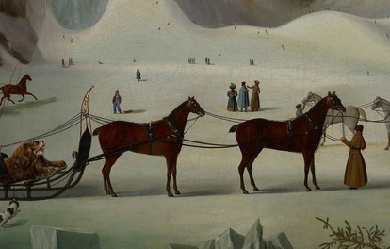

Info

Louise-Antoinette Feuardent

Jean-François Millet

1841

El J. Paul Getty Museum

Valentine Ackland (20 May 1906– 9 November 1969) was an English poet, an important figure in the emergence of modernism in twentieth-century British poetry. Life Ackland was born Mary Kathleen Macrory Ackland to Robert Craig Ackland and his wife Ruth Kathleen (née Macrory), and nicknamed “Molly” by her family. With no sons born to the family, Valentine’s father, a West End London dentist, worked at making a symbolic son of Molly, teaching her to shoot rifles and to box. This attention to Molly made her sister Joan Alice Elizabeth (b. 1898) immensely jealous. Older by eight years, Joan psychologically tormented and physically abused Molly as a way of unleashing her jealousy and anger. Molly received an Anglo-Catholic upbringing in Norfolk and a convent school education in London. In 1925 at the age of nineteen, she impetuously married Richard Turpin, a homosexual youth who was unable to consummate their marriage. Upon her marriage, she was also received into the Catholic church, a religion that she later abandoned, returned to, and then abandoned again in the last decade of her life. In less than a year, she had her marriage to Turpin annulled, and, despite numerous pleas from her family and much psychological pressure from them, never returned to a serious relationship with a man again. Alert to social mores of her day, she became aware of societal patterns of male privilege and female submission set about challenging the female gender identifications expected of her. She took to wearing men’s clothing, cut her hair in a short style called the Eton crop, and was at times mistaken for a handsome young boy. She changed her name to the androgynous Valentine Ackland when she decided to become a serious poet in the late 1920s. Her poetry appeared in British and American literary journals during the 1920s to the 1940s, but Ackland deeply regretted that she never became a noted and widely read poet. In this regard, much of her poetry was published posthumously, and she received little attention from critics until a revival of interest in her work in the 1970s. In 1930, Ackland was introduced to the short story writer and novelist Sylvia Townsend Warner, with whom she had a lifelong relationship, albeit tumultuous at times given Ackland’s increasing alcoholism and infidelities. Warner was twelve years older than Ackland, and the two lived together until Ackland’s death from breast cancer in 1969. Warner went on to outlive Ackland by nine years, dying in 1978. The pair were together for thirty-nine years. Ackland’s reflections upon her relationship with Warner and the former’s long affair with American heiress and writer Elizabeth Wade White (1908–1994), were posthumously published in For Sylvia: An Honest Account (1985). Ackland was a highly emotional woman prone to numerous self-doubts and shifts in emotions and intellectual interests. She was responsible for involving Warner in membership in the Communist Party in the 1930s and in 1937 she visited Valencia and Benicàssim within the framework of the Spanish Civil War as well as numerous socialist and pacifist activities. The two women’s involvement in the Communist Party came under investigation by the British government in the late 1930s and remained an open file until 1957, when the investigation was halted. Ackland and Warner supported the Republican cause during the Spanish Civil War, and Ackland criticised the British government for its indifference to the “sufferings of the Spanish people at the grass-roots level” in her poem "Instructions from England, 1936". Note nothing of why or how, enquire no deeper than you need into what set these veins on fire, Note simply that they bleed. After World War II, Ackland turned her attention to confessional poetry and a memoir concerning her relationship with Warner and its many emotional issues as Ackland pursued involvements with other women. At first, Warner was tolerant with her younger lover’s dalliances, but the seriousness and length of Ackland’s relationship with Elizabeth Wade White was distressing to Warner and also pushed her relationship with Ackland to the edge. Ackland’s distresses at loving two women simultaneously and of endeavouring to balance her feelings for each woman with the responsibilities and commitments of her primary relationship with Warner are presented openly in Ackland’s poetry and in her memoir of this period. Ackland was struggling with additional doubts and conflicts during this period as well. She continued to battle her alcoholism, and she was undergoing shifts in her political and religious alliances. Doubts about her sexual identity and her identity as a poet as well as about her Christian faith and her political convictions are evident in her poetry. In 1934, Ackland and Warner produced a volume of poetry, “Whether a Dove or a Seagull” that was an unusual and democratic experiment in writing as none of the poems is ascribed to either author. The volume was also an attempt by Warner to introduce Ackland to publication since Warner had an already established reputation as a novelist, and her work was widely read in the 1930s. The volume was controversial for its frank discussion of lesbianism at a time and in a society in which lesbianism was regarded as deviant and immoral behaviour. In 1937, Ackland and Warner moved from rural Dorset to a house near Dorchester. Both became involved with Communist ideals and issues, with Ackland writing a column called “Country Dealings” concerning rural poverty for the “Daily Worker” and the “Left Review.” In 1939, the two women attended the American Writers Congress in New York City to consider the loss of democracy in Europe and returned when World War II broke out. Ackland’s poetry of this period attempted to capture the political dynamics she saw at work, but she had a difficult time as a poet mastering the craft of combining political polemics with her natural tendency toward lyrical expression. In a similar vein, her distress over the loss of democracy in Europe became a broader identification with Existentialism and the sense that the human condition itself was hopeless. Death Ackland died on 9 November 1969 from breast cancer that had metastasised to her lungs. She was buried together with Sylvia Townsend Warner in St Nicholas’s churchyard at Chaldon Herring with the inscription from Horace Non omnis moriar (Ode III.30, “I shall not wholly die”) on her gravestone. Critical assessment Ackland’s poetry—largely neglected after the 1940s—came into a resurgence of interest with the emergence of both women’s studies and of lesbian literature. Contemporary critical reaction finds much to value in Ackland’s poetry and confessional writings, which are of historical interest to the development of self-reflective, modernist poetry, and to the political and cultural issues of the 1930s and 1940s. One example of a recent critical analysis is Wendy Milford’s 1988 study, This Narrow Place: Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland. With regard to her self-reflection as a poet, Ackland exhibits themes and explorations similar to poets like Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton. Of interest, too, is Ackland’s explorations of terminal illness as her life was drawing to a close from cancer. In her later years, Ackland turned from Catholicism to Quaker beliefs and also to involvement with issues of environmentalism. In overall assessment, Milford considers the two-minds at work in Ackland’s work. She cites as examples Ackland’s focus on optimism and dread, the longing for emotional closeness and the fear of intimacy, self-assertion and self-negation, the search for privacy and solitude amidst the longing for connection and social acceptance as a lesbian and as a noteworthy poet. In this regard, Ackland shares much thematically—though not in artistic achievement—with metaphysical poets like John Donne and Philip Larkin in the effort to see personal experience from multiple perspectives and never fully resting with one perspective or another. A contemporary examination of Ackland’s poetry and essays was published by Carcanet Press in 2008 titled Journey from Winter: Selected Poems. The volume is edited by Frances Bingham, who also provides a contextual and critical introduction. Bibliography * Whether a Dove or a Seagull (1934) volume of poetry with Sylvia Townsend Warner * Twenty-Eight Poems (1957) privately printed in London * Later Poems by Valentine Ackland (1970) * The Nature of the Moment (1973) * Further Poems of Valentine Ackland (1978) * For Sylvia: An Honest Account (1985) a memoir of Ackland’s relationship with Sylvia Townsend Warner * This Narrow Place: Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland 1931–1951, by Wendy Mulford (1988) * Jealousy in Connecticut, by Susanna Pinney (1998) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valentine_Ackland

Bernard Patrick O’Dowd (11 April 1866– 1 September 1953) was an Australian activist, educator, poet, journalist, and author of several law books and poetry books, born in Beaufort, Victoria. O’Dowd worked as an assistant-librarian and later Chief Parliamentary Draughtsman in the Supreme Court at Melbourne for 48 years; he was also a co-publisher and writer for the radical paper Tocsin. Bernard O’Dowd lived to age 87.

Carl Rakosi (November 6, 1903– June 25, 2004) was the last surviving member of the original group of poets who were given the rubric Objectivist. He was still publishing and performing his poetry well into his 90s. Early life Rakosi was born in Berlin and lived there and in Hungary until 1910, when he moved to the United States to live with his father and stepmother. His father was a jeweler and watchmaker in Chicago and later in Gary, Indiana. The family lived in semi-poverty but contrived to send him to the University of Chicago and then to the University of Wisconsin–Madison. During his time studying at the university level, he started writing poetry. On graduating, he worked for a time as a social worker, then returned to college to study psychology. At this time, he changed his name to Callman Rawley because he felt he stood a better chance of being employed if he had a more American-sounding name. After a spell as a psychologist and teacher, he returned to social work for the rest of his working life. Early writings At the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Rakosi edited the Wisconsin Literary Magazine. His own poetry at this stage was influenced by W. B. Yeats, Wallace Stevens, and E. E. Cummings. He also started reading William Carlos Williams and T. S. Eliot. By 1925, he was publishing poems in The Little Review and Nation. Pound and the Objectivists By the late 1920s, Rakosi was in correspondence with Ezra Pound, who prompted Louis Zukofsky to contact him. This led to Rakosi’s inclusion in the Objectivist issue of Poetry and in the Objectivist Anthology. Rakosi himself had reservations about the Objectivist tag, feeling that the poets involved were too different from each other to form a group in any meaningful sense of the word. He did, however, especially admire the work of Charles Reznikoff. Later career Like a number of his fellow Objectivists, Rakosi abandoned poetry in the 1940s. After his 1941 Selected Poems he dedicated himself to social work and apparently neither read nor wrote poetry. Years earlier, shortly after his twenty-first birthday, Rakosi had legally changed his name to Callman Rawley, believing that he would not find work with his foreign-sounding name. Under his adopted name, he served as head of the Minneapolis Jewish Children’s and Family Service from 1945 until his retirement in 1968. A letter from the English poet Andrew Crozier about his early poetry was the trigger that started Rakosi writing again. His first book in 26 years, Amulet, was published by New Directions in 1967 and his Collected Poems in 1986 by the National Poetry Foundation. These were followed by several more volumes and by readings across the United States and Europe. In early November 2003, Rakosi celebrated his 100th birthday with friends at the San Francisco Public Library. Upon his death Jacket Magazine editor John Tranter observed the following: Poet Carl Rakosi died on Friday afternoon June 25 at the age of 100, after a series of strokes, in his home in San Francisco. My wife Lyn and I were passing through California in November 2003, and we stopped by to have a coffee with Carl at his home in Sunset. By a lucky coincidence, it happened to be his 100th birthday. He was, as always, kind, thoughtful, bright and alert, and as sharp as a pin. We felt privileged to know him. External links Rakosi at Modern American Poetry The Carl Rakosi Papers in the Mandeville Special Collections Library at UC San Diego Carl Rakosi Reading and Interview on KPFA’s Ode To Gravity, 13 May 1971 (from The Internet Archive) Obituary in The Guardian, UK Carl Rakosi feature at Jacket Magazine includes Rakosi in conversation with Tom Devaney & Olivier Brossard; link to audio recordings at University of Pennsylvania, and poems, dedications & remembrances from Jane Augustine, Robert Creeley, Laurie Duggan, Michael Heller and Kent Johnson “Add-Verse” a poetry-photo-video project Rakosi participated in References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Rakosi

Henry Livingston, Jr. (October 13, 1748 - February 29, 1828) has been proposed as being the uncredited author of the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas”, more popularly known (after its first line) as “The Night Before Christmas.” Credit for the poem was taken in 1837 by Clement Clarke Moore, a Bible scholar in New York City, nine years after Livingston’s death. It wasn’t until another twenty years that the Livingston family knew of Moore’s claim, and it wasn’t until 1900 that they went public with their claim. Since then, the question has been repeatedly raised and argued by experts on both sides. In 2000, Professor Don Foster made a strong case for Livingston’s authorship, while Professor Stephen Nissenbaum and manuscript dealer Seth Keller, who had owned a Moore manuscript copy of the poem at the time of Foster’s book, argued for Moore. Fifteen years later New Zealand scholar and Emeritus Professor of English Literature MacDonald P. Jackson invested over a year of research statistically analyzing the poetry of both men. His conclusion: “Every test, so far applied, associates ”The Night Before Christmas" much more closely with Livingston’s verse than with Moore’s.” Biography Livingston was born on October 13, 1748, in Poughkeepsie, New York, to Henry Livingston, Sr. and Susannah Conklin. In 1774, Livingston married Sarah Welles, the daughter of Reverend Noah Welles, the minister of the Stamford, Connecticut Congregational Church. Their daughter Catherine was born shortly before Livingston joined the army on a six months’ enlistment. In 1776, their son Henry Welles Livingston was born; the child was fatally burned at the age of fourteen months and, when another son was born, he was given the same name, according to the common practice of necronyms. Livingston farmed. Sarah died in 1783, and the children were boarded out. During this period Livingston began writing poetry. Over the next ten years, Livingston was occupied with poetry and drawings for his friends and family, some of which ended up in the pages of New York Magazine and the Poughkeepsie Journal. Although he signed his drawings, his poetry was usually anonymous or signed simply “R”. Ten years to the day after Sarah’s death, Livingston remarried. Jane Patterson, at 24, was 21 years younger than her husband. Their first baby arrived nine months after the wedding. After that, the couple bore seven more children. It was for this second family that Henry Livingston is believed by some to have written the famous poem known as “A Visit from St. Nicholas” or “The Night Before Christmas”. This famous Christmas poem first appeared in the Troy Sentinel on December 23, 1823. There seems to be no question that the poem came out of the home of Clement Moore, and the person giving the poem to the newspaper, without Moore’s knowledge, certainly believed the poem had been written by Moore. However, several of Livingston’s children remembered their father reading that very same poem to them fifteen years earlier. As early as 1837, Charles Fenno Hoffman, a friend of Moore’s, put Moore’s name on the poem. In 1844, Moore published the poem in his own book, Poems. At multiple times in his later life, Moore wrote out the now famous poem in longhand for his friends. Dispute over authorship Because the poem was first published anonymously, various editions were for many years published both with and without attribution. As a result, it was only in 1859, 26 years after the poem first appeared in print, that Henry’s family discovered that Moore was taking credit for what they believed to be their father’s poem. That belief went back many years. Around 1807, Henry’s sons Charles and Edwin, as well as their neighbor Eliza (who would later marry Charles) remembered their father’s reading the poem to them as his own. Following their father’s death in 1828, Charles claimed to have found a newspaper copy of the poem in his father’s desk, and son Sidney claimed to have found the original handwritten copy of the poem with its original crossouts. The handwritten copy of the poem was passed from Sidney, on his death, to his brother Edwin. However, the same year that the family discovered Moore’s claim of authorship, Edwin claimed to have lost the original manuscript in a house fire in Wisconsin, where he was living with his sister Susan. By 1879, five separate lines of Henry’s descendants had begun to correspond among themselves, trying to compare their family stories in the hope that someone had some proof that could be brought forward, but there was no documentation beyond family stories. In 1899, even without proof, Sidney’s grandson published the first public claim of Henry’s authorship in his own newspaper on Long Island. The claim drew little attention. In 1920, Henry’s great grandson, William Sturgis Thomas became interested in the family stories and began to collect the memories and papers of existing descendants, eventually publishing his research in the 1919 issue of the Duchess County Historical Society yearbook. Thomas provided this material to Winthrop P. Tryon for his article on the subject in the Christian Science Monitor on August 4, 1920. Later, Moore descendants arranged to have an elderly family connection, Maria Jephson O’Conor, depose about her memories of Moore’s claim of authorship. On independent grounds, Don Foster, Professor of English at Vassar, has argued that Livingston is a more likely candidate for authorship than Moore. Foster’s claim, however, has been countered by document dealer and historian Seth Kaller, who once owned one of Moore’s original manuscripts of the poem. Kaller has offered a point-by-point rebuttal of both Foster’s linguistic analysis and external findings, buttressed by the work of autograph expert James Lowe and Dr. Joe Nickell, author of Pen, Ink and Evidence. There is no proof that Livingston himself ever claimed authorship, nor has any record ever been found of any printing of the poem with Livingston’s name attached to it. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Livingston,_Jr.

Augustus Montague Toplady (4 November 1740– 11 August 1778) was an Anglican cleric and hymn writer. He was a major Calvinist opponent of John Wesley. He is best remembered as the author of the hymn “Rock of Ages”. Three of his other hymns– “A Debtor to Mercy Alone”, “Deathless Principle, Arise” and “Object of My First Desire”– are still occasionally sung today, though all three are far less popular than “Rock of Ages”. Background and early life, 1740–55 Augustus Toplady was born in Farnham, Surrey, England in November 1740. His father, Richard Toplady, was probably from Enniscorthy, County Wexford in Ireland. Richard Toplady became a commissioned officer in the Royal Marines in 1739; by the time of his death, he had reached the rank of major. In May 1741, shortly after Augustus’ birth, Richard participated in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias (1741), the most significant battle of the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739–42), during the course of which he died, most likely of yellow fever, leaving Augustus’ mother to raise the boy alone. Toplady’s mother, Catherine, was the daughter of Richard Bate, who was the incumbent of Chilham from 1711 until his death in 1736. Catherine and her son moved from Farnham to Westminster. He attended Westminster School from 1750 to 1755. Trinity College, Dublin: 1755–60 In 1755, Catherine and Augustus moved to Ireland, and Augustus was enrolled in Trinity College, Dublin. Shortly thereafter, in August 1755, the 15-year-old Toplady attended a sermon preached by James Morris, a follower of John Wesley, in a barn in Codymain, co. Wexford (though in his Dying Avowal, Toplady denies that the preacher was directly connected to Wesley, with whom he had developed a bitter relationship). He would remember this sermon as the time at which he received his effectual calling from God. Having undergone his religious conversion under the preaching of a Methodist, Toplady initially followed Wesley in supporting Arminianism. In 1758, however, the 18-year-old Toplady read Thomas Manton’s seventeenth-century sermon on John 17 and Jerome Zanchius’s Confession of the Christian Religion (1562). These works convinced Toplady that Calvinism, not Arminianism, was correct. In 1759, Toplady published his first book, Poems on Sacred Subjects. Following his graduation from Trinity College in 1760, Toplady and his mother returned to Westminster. There, Toplady met and was influenced by several prominent Calvinist ministers, including George Whitefield, John Gill, and William Romaine. It was John Gill who in 1760 urged Toplady to publish his translation of Zanchius’s work on predestination, Toplady commenting that “I was not then, however, sufficiently delivered from the fear of man.” Church ministry: 1762–78 In 1762, Edward Willes, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, ordained Toplady as an Anglican deacon, appointing him curate of Blagdon, located in the Mendip Hills of Somerset. Toplady wrote his famous hymn “Rock of Ages” in 1763. A local tradition– discounted by most historians– holds that he wrote the hymn after seeking shelter under a large rock at Burrington Combe, a magnificent ravine close to Blagdon, during a thunderstorm. Upon being ordained priest in 1764, Toplady returned to London briefly, and then served as curate of Farleigh Hungerford for a little over a year (1764–65). He then returned to stay with friends in London for 1765–66. In May 1766, he became incumbent of Harpford and Venn Ottery, two villages in Devon. In 1768, however, he learned that he had been named to this incumbency because it had been purchased for him; seeing this as simony, he chose to exchange the incumbency for the post of vicar of Broadhembury, another Devon village. He would serve as vicar of Broadhembury until his death, although he received leave to be absent from Broadhembury from 1775 on. Toplady never married, though he did have relationships with two women. The first was Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, the founder of the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion, a Calvinist Methodist series of congregations. Toplady first met Huntingdon in 1763, and preached in her chapels several times in 1775 during his absence from Broadhembury. The second was Catharine Macaulay, whom he first met in 1773, and with whom he spent a large amount of time in the years 1773–77. Animals and Natural World Toplady was a prolific essayist and letter correspondent and wrote on a wide range of topics. He was interested in the natural world and in animals. He composed a short work “Sketch of Natural History, with a few particulars on Birds, Meteors, Sagacity of Brutes, and the solar system”, wherein he set down his observations about the marvels of nature, including the behaviour of birds, and illustrations of wise actions on the part of various animals. Toplady also considered the problem of evil as it relates to the sufferings of animals in “A Short Essay on Original Sin”, and in a public debate delivered a speech on “Whether unnecessary cruelty to the brute creation is not criminal?”. In this speech he repudiated brutality towards animals and also affirmed his belief that the Scriptures point to the resurrection of animals. Toplady’s position about animal brutality and the resurrection were echoed by his contemporaries Joseph Butler, Richard Dean, Humphry Primatt and John Wesley, and throughout the nineteenth century other Christian writers such as Joseph Hamilton, George Hawkins Pember, George N. H. Peters, Joseph Seiss, and James Macauley developed the arguments in more detail in the context of the debates about animal welfare, animal rights and vivisection. Calvinist controversialist: 1769–78 Toplady’s first salvo into the world of religious controversy came in 1769 when he wrote a book in response to a situation at the University of Oxford. Six students had been expelled from St Edmund Hall because of their Calvinist views, which Thomas Nowell criticised as inconsistent with the views of the Church of England. Toplady then criticised Nowell’s position in his book The Church of England Vindicated from the Charge of Arminianism, which argued that Calvinism, not Arminianism, was the position historically held by the Church of England. 1769 also saw Toplady publish his translation of Zanchius’s Confession of the Christian Religion (1562), one of the works which had convinced Toplady to become a Calvinist in 1758. Toplady entitled his translation The Doctrine of Absolute Predestination Stated and Asserted. This work drew a vehement response from John Wesley, thus initiating a protracted pamphlet debate between Toplady and Wesley about whether the Church of England was historically Calvinist or Arminian. This debate peaked in 1774, when Toplady published his 700-page The Historic Proof of the Doctrinal Calvinism of the Church of England, a massive study which traced the doctrine of predestination from the period of the Early Church through to William Laud. The section about the Synod of Dort contained a footnote identifying five basic propositions of the Calvinist faith, arguably the first appearance in print of the summary of Calvinism known as the “five points of Calvinism”. The relationship between Toplady and Wesley that had initially been cordial, involving exchanges of letters in Toplady’s Arminian days, became increasingly bitter and reached its nadir with the “Zanchy affair”. Wesley took exception to the publication of Toplady’s translation of Zanchius’s work on predestination in 1769 and published, in turn, an abridgment of that work titled “The Doctrine of Absolute Predestination Stated and Asserted”, adding his own comment that “The sum of all is this: One in twenty (suppose) of mankind are elected; nineteen in twenty are reprobated. The elect shall be saved, do what they will; the reprobate will be damned, do what they can. Reader believe this, or be damned. Witness my hand.” Toplady viewed the abridgment and comments as a distortion of his and Zanchius’s views and was particularly enraged that the authorship of these additions were attributed to him, as though he approved of the content. Toplady published a response in the form of “A Letter to the Rev Mr John Wesley; Relative to His Pretended Abridgement of Zanchius on Predestination”. Wesley never publicly accepted any wrongdoing on his part and seemingly denied his authorship of the comments contained in his abridgement when, in his 1771 work “The Consequenses Proved” that responded to Toplady’s letter, he ascribed his additions to Toplady. Subsequently Wesley avoided direct correspondence with Toplady, famously stating in a letter of 24 June 1770 that “I do not fight with chimney-sweepers. He is too dirty a writer for me to meddle with. I should only foul my fingers. I read his title-page, and troubled myself no farther. I leave him to Mr Sellon. He cannot be in better hands.” Last years Toplady spent his last three years mainly in London, preaching regularly in a French Calvinist chapel at Orange Street (off of Haymarket), most spectacularly in 1778, when he appeared to rebut charges being made by Wesley’s followers that he had renounced Calvinism on his deathbed. Toplady died of tuberculosis on 11 August 1778. He was buried at Whitefield’s Tabernacle, Tottenham Court Road. Hymns Compared with Christ, in all beside n. 760 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1772) Deathless spirit, now arise n. 1381 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776) Holy Ghost, dispel our sadness n. 80 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776). Modernising of John Christian Jacobi’s translation (1725) of Paul Gerhardts hymn from 1653. How happy are the souls above n. 1434 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776) (? A. M. Topladys text) Inspirer and hearer of prayer n. 30 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1774) O thou, that hear’st the prayer of faith n. 642 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1176) Praise the Lord, who reigns above n. 160 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1759) Rock of ages, cleft for me n. 697 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776) Surely Christ thy griefs hath borne n. 443 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1759) What, though my frail eye-lids refuse n. 29 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1774) When langour and disease invade n. 1032 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1778) Your harps, ye trembling saints n. 861 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1772) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus_Toplady

Kathleen Faragher (1904–1974) was the most significant and prolific Manx dialect author of the mid twentieth century. She is best known for her poems first published in the Ramsey Courier and collected into five books published between 1955 and 1967. She was also a prolific short story writer and playwright. Her work is renowned for its humour born of a keen observation of Manx characters, and for its evocative portrayal of the Isle of Man and its people. Life Kathleen Faragher was born in 1904 in Ramsey, Isle of Man, to Joseph and Catherine Anne Faragher, owners of a grocer and provision merchant business on Approach Road. Kathleen was the youngest of five children: Laurence (who died in Gibraltar in 1944 during WWII), Fred (later manager of Martin’s Bank, Peel), Joseph (who took over the family business but died in 1946), Evelyn (who emigrated to Auckland, New Zealand, where she died in 1949) and herself. Kathleen Faragher was raised in Ramsey until about 1924, when she moved to London to take up a business career. After 25 years working in London, ill-health forced her into early retirement, whereupon she returned to live on the Isle of Man in October 1949. Faragher lived first in Ramsey but eventually moved to Maughold, finally coming to live near to the Dhoon Church in Glen Mona. Poetry Faragher’s first poem, 'Blue Point’, was published in the Ramsey Courier on 14 October 1949. The poem was written whilst in Kent and sent to the paper, who surprised Faragher in accepting it, although it was not published until she had returned to live on the island. This poem was different in style to Faragher’s subsequent work and it was only published in her third book of poetry, Where Curlews Call, in 1959, by which time it had been substantially rewritten. Her next poem, 'Maughold Head’, was published at the start of February 1950, after which her poems were published regularly in the Ramsey Courier. Her first published poem in the Anglo-Manx dialect was 'A Lament’, which appeared in September 1950. Her poems were quickly picked up as special evocations of the Isle of Man and they were recited at meetings of Manx Societies in England alongside poems by the Manx National Poet, T. E. Brown, as early as November 1951. Her poems, 'Maughold Head’ and 'In Exile’, were set to music by C. Sydney Marshall and had been cut to record by February 1960. Her first book of poems, Green Hills by the Sea, was published in February 1955 by The Ramsey Courier Ltd. The book’s title is a reference to the popular song, 'Ellan Vannin’, composed from a poem by Eliza Craven Green. The book was described as displaying Faragher’s “deep insight into Manx feelings and a nostalgic love of the old folk and ways” by George Bellairs. The collection opened with 'Land of My Birth’, which she described as “the greatest compliment she can pay to the Manx people” and with which she usually ended her recitals. I love this purple-misted Isle, This land where I was born. The gorse-clad hills and bracken tops, The fields of waving corn. [...] But best of all I love to hear The gentle, lilting voice Of kindly Manx folk greeting me: It makes my heart rejoice, To feel once more the friendly hand, To hear the welcome warm, To look into each smiling face And know I have come home. Her second collection, This Purple-Misted Isle, was published in October 1957. The title was another reference to her forebears of Manx literature, this time to T. E. Brown, a reference continued within the collection with Faragher’s 'The Immortal “Kitty”' paying homage to Brown’s 'Kitty o’ the Sherragh Vane’ from his Fo’c’s’le Yarns. The collection had a Foreword by the Lieutenant Governor, Ambrose Flux Dundas. It proved to be very popular, having to be reprinted by the end of the year, and by the end of 1959 a third print had also almost sold out. This collection included 'The Homecomer’, which displays her distinctive Anglo-Manx conversational style: [...] “It isn’ me dyin’ that I min’, boy,” She said as she sat by her bed; “I’d go peaceful if it wasn’ for thinkin’ Ye’ll be managin’ so maul when I’m dead.” An’ Billy sthroked her cheek– so the tale goes – An’ whispered all lovin’ an’ low, “Dunt be grievin’, Nellie Kate; theer’s no need to gel, To worry about me when yer go! For theer’s the nices’ li’l wumman in Laxaa That I’ve had me eye on this las’ bit; She’ll look after me well, I can tell yer, So take yer res’, Nellie Kate, an’ dunt fret!” My gough! She gorrup from that bed theer Like an arra shot straight from the bow! Ay! an’ Billy himself was years buried ‘Fore herself in the en’ had to go! [...] By 1959 Faragher’s poems had been heard on BBC Radio a number of times, recited both by herself and by others. It was in October of that year that her third collection was released, Where Curlews Call, bearing a perceptive Preface by Sir Ralph Stevenson: “Our mother tongue has been overlaid by a stereotyped accent [...]. The Manx lilt [...] is all too rapidly fading. She does her best in these poems to keep it alive and at the same times gives a warm and human picture of our farms and crofts and the kindly folk who live in them. For this, if for nothing else, she has earned our gratitude.” Her subsequent collections of poetry were These Fairy Shores (1962) and English and Manx Dialect Poems (1967). Faragher’s poems can be predominantly categorised into two types: light-humoured dialect vignettes or lyrical descriptions of the Isle of Man. Her poems are distinctive in Manx literature in being prevailingly from or of a female perspective and based within the family or home environment. Theatre and prose As early as 1951 Faragher had been experimenting with extending her conversational monologue Anglo-Manx poems into theatrical dialogues for performance. In 1964 four such 'character sketches’ were published as Kiare Cooisghyn. As was distinctive of her dialect poetry, all of these pieces were written for middle-aged or elderly female characters and used a very tender humour born of a close observation of Manx character. Something of this is shown in the first 'duologue’ from the collection, 'The Caffy’ in which two women discuss the new café in town: [...] Mrs K. An’ what like was the china? Gran’ mighty I suppose? Mrs C. Aw! somethin’ awful that was! Rale indacent, in fac’. A whole lorra naked childher flyin’ about on the plates shootin’ bows an’ arras. Mrs K. Aw! them 'ud be l’il Cupids. Mrs C. Li’l Cupids? Li’l divils, more like! Why wan o’ them was the dead spit o’ that young dirt Kermid’s yandher! Ay! skeetin’ up at me through the gravy he was– enough to turn yer! [...] She came to concentrate on prose towards the end of her life, publishing By The Red Fuchsia Tree in 1967, a collection of short stories interspersed with reprints of poems from her earlier collections. This was followed by a long series of short dialect stories published under the pseudonym, “Kirree Ann”, in the Ramsey Courier at a rate of almost one a week over the last two years of her life. This output of nearly 100 short stories makes her the most prolific Manx short story writer of the twentieth Century. Death and legacy Kathleen Faragher died in 1974, on the same day as her final story was published in the Ramsey Courier. She was buried in the family plot in Maughold churchyard, a graveyard also associated with other important Manx writers such as T. E. Brown, Hall Caine, Cushag and William Kennish. Six years after her death, her friend, Constance Radcliffe, the leading authority on the local history of Ramsey and Maughold, wrote of Faragher’s work that: “In all her works she expressed her affection for a Manx way of life which has only just disappeared, her kindly humour based on acute observation of people’s idiosyncrasies, and her deep and abiding love of the island itself.” Her work continues to be popularly performed in recitals on the Isle of Man, despite none of her books having been republished after her death, and her “Kirree Ann” stories having never been collected. In 2015 a project to record the memories of those who knew and remember Faragher was launched. Funded by Culture Vannin, it is envisioned to tie in with the Culture Vannin oral history programme, but also to reach more widely to collect unpublished works, memorabilia or other artefacts that might be uncovered. In introducing the initiative, the project organiser gave an estimation of Faragher’s work in relation to Manx literature: “the importance of her work to the Isle of Man would be hard to overestimate. It would be a tragedy for Manx culture if we did not do everything in our power to preserve all we can of her memory.” Publications * Green Hills by the Sea. Ramsey: The Ramsey Courier Ltd. 1954. * This Purple-Misted Isle. Ramsey: The Ramsey Courier Ltd. 1957. * Where Curlews Call. Ramsey: The Ramsey Courier Ltd. 1959. * These Fairy Shores. Ramsey: The Ramsey Courier Ltd. 1962. * Kiare Cooisghyn. Ramsey: The Ramsey Courier Ltd. 1964. * English and Manx Dialect Poems. Douglas: Norris Modern Press. 1967. * By The Red Fuchsia Tree. Douglas: The Norris Modern Press. 1967. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kathleen_Faragher